Eugene Stoner was an absolute genius. The AR-15 and AR-10 pattern rifles he designed have been more successful than nearly any other rifle design in history. Eugene Stoner didn’t stop there and he continued to create guns until he died. He worked for various companies, including Knight’s Armament, and Cadillac Gage. Stoner went to Caddilac Gage in the 1960s with a new design in hand, that new design being the Stoner 63. I’d like to say Stoner 63 rifle, or Stoner 63 machine gun, or Stoner 63 carbine, but I can’t.

Limiting it to just one type of firearm would be an inaccurate description. The Stoner 63 was unlike any weapon we’ve ever seen then and pretty much since. Eugene designed the Stoner 63 to be all of those things. It would be one gun to do it all, one receiver that could accommodate an extremely wide variety of configurations.

It was 1962, and Eugene had sold the AR-15 design to Colt and moved on to new and greener pastures. He worked with Cadillac Gage to bring the Stoner 63 to life. Initially, we had the Stoner 62, which was a 7.62 NATO version of the weapon. They decided to move to the 5.56 cartridge because it was becoming readily apparent that the little 5.56 round was seeing worldwide adoption. Thus the Stoner 63 came to be in 1963.

The Stoner 63 – At Its Core

At its core, the Stoner 63 is a long-stroke gas piston system, capable of both semi and fully automatic modes, and utilized the 5.56 caliber round. Other than that, everything else was on the table depending on the Stoner 63’s configuration.

Immediately the design got some eyes on it. The Army and Marines both wanted to test the design. The Army put it through a series of trials that forced an unreasonable expectation of ammunition on it. They wanted it to function with ammo that was too underpowered to function even in an M16, continuing their history of bad ammunition choices.

After months the Army sent back their recommendations. The Army wanted a two-position fire selector with separate safety, a stainless steel gas cylinder, modifications to the belt feed mechanism, and ejection port dust covers. Cadillac Gage and Eugene Stoner obliged, and the new models were designated the Stoner 63A.

All The Many Faces of The Stoner 63

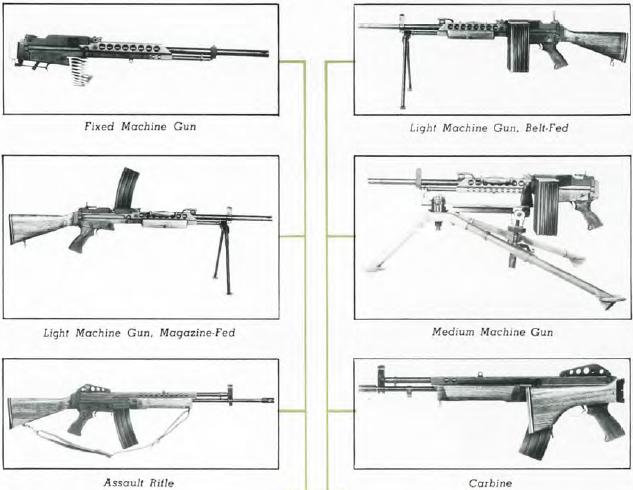

Rifle and Carbine

The standard rifle variants feed from a bottom-located magazine. The magazine resembles an AR magazine but is proprietary and rocks in and locks like an AK47. This was necessitated by the lack of a magazine well. Capable of both semi-automatic fire and full-automatic fire. The rifle wears a 20-inch barrel, and the carbine uses a 15.7-inch barrel.

Automatic Rifle

The Automatic rifle version places the magazine on top of the gun, much like a Bren gun. The sights are offset to the side, also like a Bren gun. The gun functioned off an open bolt and was full auto only. The Marines tested it in 1967 and quickly discarded it as a concept.

[Editor’s note: They discarded it as a concept then, but look at the IAR and tell me we didn’t circle back to the magazine fed auto-rifle concept.]

Light Machine Gun

The Stoner 63 saw the most success with the light machine gun variant of the gun. The light machine gun version feeds with a belt and fires from an open bolt configuration. The LMG variant utilized a 75, 100, or 150 round drum to contain the belt of ammo. The LMG featured a quick change barrel as well.

Medium Machine Gun

I put ‘medium’ in quotations because a 5.56 machine gun isn’t necessarily a medium machine gun. The light machine gun became the medium machine gun when it was fitted with an M122 tripod adapter.

Fixed Machine Gun

This variant was also a light machine gun, but the buttstock and pistol grip are cast away. The fixed machine gun uses a solenoid to fire it and would be mounted to defensive positions and on vehicles. If you ever wonder why the Stoner 63 has a hole in the trigger, it’s to accommodate the solenoid for remote activation.

Commando

The Commando variant is what happens when you add a shorter but heavier barrel to the LMG variant that is not quick-change capable. The Commando variant saw lots of action with the Navy SEALs in Vietnam. Stoner trimmed the barrel to 15.7 inches, and we saw a good amount of weight reduction.

Survival Rifle

The Survival rifle variant never left the prototype phase and featured a short carbine barrel, a trimmed-down pistol grip, a folding stock, and very simple sights.

How Did It Work?

The Stoner 63 system utilized a common receiver that could be configured to various configurations. Armed forces could use a weapon like a rifle or a carbine, or convert the receiver to a belt-fed design for a light machine gun role, or remove the stock and pistol grip and toss it on a vehicle. They could do all of this with one common receiver.

To be clear, this system was not field serviceable. Trained armorers configured the weapon as needed by the force wielding them. There were several spare parts, and we know how fast Joe could lose small parts in the field.

The key to the Stoner 63’s design was the fact you could flip the receiver one way or another to accommodate different configurations. When you convert a magazine version to belt-fed, you flip the receiver over to do so. Sights are removed and replaced with trigger groups, the LRBHO is removed to accommodate a belt, and various fire control groups allowed you to change how the Stoner 63 functioned.

Simple and Ingenious

The trigger and fire control groups are rather ingenious. It’s a complete trigger group that pops on and off. It’s not small parts you are forced to install one by one. Instead, you just swapped complete trigger groups, which took no time at all. Stoner designed one trigger group to function with a closed bolt rifle or carbine variant; Stoner configured the second for open-bolt machine guns.

When swapping between closed and open bolt variants, you also make some slight tweaks to the bolt carrier and piston group. A small piece at the end of the device must be in a particular position dependent on the operating mechanism. All armorers needed to flip was this small oddly-shaped square-like part at the rear of the piston to allow for open-bolt or closed-bolt firing.

When armorers flipped this device, it changed how the bolt operated with the hammer-fired rifle trigger group and the open bolt trigger group. The firing pin configuration changed as well. In the rifle setting, it free-floated. In the open bolt setting, the firing pin locked into a fixed position.

Ergonomics Varied

Multiple charging handles were produced for the Stoner 63. One universal design sat on the left-hand side when utilized as a rifle and on the right-hand side when utilized on a machine gun. Over time a vertically mounted charging handle was adopted to sit on the top or bottom depending on the configuration and what the user desired.

Most used a top charging handle, but the SEALs adopted a bottom charging handle and modified charging handle for the MK23 machine gun variant. Numerous stocks allowed for fixed or folding designs, and any shoulder-fired variant could use either stock depending on user or unit preference.

Did the Stoner 63 Succeed?

Marines brought a couple hundred Stoner 63s to Vietnam. According to Forgotten Weapons, they brought 27 machine guns, 12 carbines, and 135 rifles. The machine guns varied between the automatic rifle and belt-fed variant. They quickly discarded the automatic rifle version because they found it rather useless.

Their testing found the Stoner 63 to be somewhat finicky and reliant on lots of maintenance and lube to run. Marines found it finicky, but SEALs loved it.

Seals adopted the Stoner 63 Commando variant as the Mk23 and used the gun up into the early 1980s. Of all the variants, the light machine gun version kicked the most ass. Heck, even by today’s standard, the 11.7-pound belt-fed machine gun is lightweight. The SEAL’s Commando variant weighed a mere 10.5 pounds.

Light Even Today

The Stoner 63 outfitted Special Ops troops with a lightweight machine gun. It was much lighter than the M60 and even lighter than the M249 SAW. Hell, FN just announced the Evolys light machine gun and it weighs 12.12 pounds.

The Stoner 63 was way ahead of its time, and it clearly demonstrated just how adaptable a firearm could be. We don’t have a modern Stoner 63, but we can certainly see its influence on light machine guns and squad support weapons.

Oddly enough, Eugene Stoner’s AR 15 kit has largely become the one receiver for every gun. The AR 15 lower receiver offers us rifles, carbines, SMGs, automatic rifles, DMRs, and even belt-fed LMGs. Regardless of its success or lack thereof, the Stoner 63 is a fascinating piece of machinery, and I’d be curious to see what a modern variant would look like.