We all love the M16 and have a mostly general disdain for the M14, but what about the middle child? Did the military ever field and adopt an M15? The answer is yes, an M15 exists. As a fellow middle child, I can most certainly relate to the feeling of being ignored and pushed to the side. While everyone shouts about the M14 and the M16 from the rooftops, the poor M15 sits long forgotten.

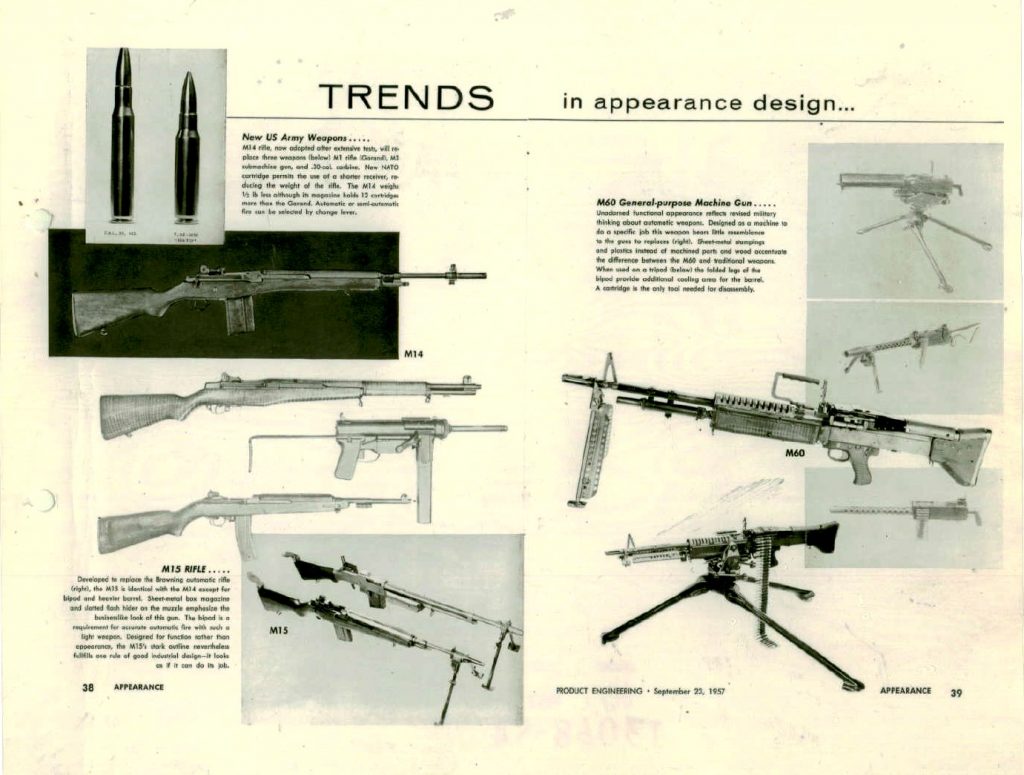

The M15 was a 1950s project that was developed around the same time as the M14. Predictably the M14 came first. The intent of the M14 was to create one rifle to fill the role of the BAR, the M1 Garand, and the Thompson. That’s a lot of different guns to replace, and the Army quickly figured out you really couldn’t do that.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

They began to develop the M15 as a replacement for the BAR. The BAR provided fire team support and suppressive fire to allow the units the move. WW2 showed the value of fire and maneuver tactics and that the average squad needed automatic firepower. Thus, they needed a squad automatic. We were a few decades away from the M249 SAW. With the M14 already developed they turned to their latest creation to replace the BAR.

The M15 – A Squad Automatic Rifle

The USMC adopted an Infantry Automatic Rifle rather recently, but the concept of a rifle in the fire support role obviously isn’t new. The Army and Marine Corps developed the M15 as a heavy version of the BAR. The M14 was selective fire, and so was the M15.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Development of the M15 essentially saw the military converting the M14 into a BAR. Although the M15 would be significantly lighter. The M15 would weigh 13.5 pounds, and the M1918A2 weighed 19 pounds. Six pounds was a nice reduction in weight.

Development saw the addition of a heavy barrel to help with increased heat and to maintain sustained fire. The stock was strengthened significantly to eat up the recoil of the 7.62 NATO in full auto. A bipod was added to help with stability, and a hinged butt plate was added to help keep the rifle locked in the shoulder. They experimented with a rate reducer, but they found that the rate reducer did not affect accuracy, so it was eliminated.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The work was completed in 1954, and the firearm was known as the T44E5 model. By 1957 the weapon was adopted, but by 1959 the weapon had been discontinued. The M15 was less successful than the M14, and that’s impressive.

Enter The M14E2 /M14A1

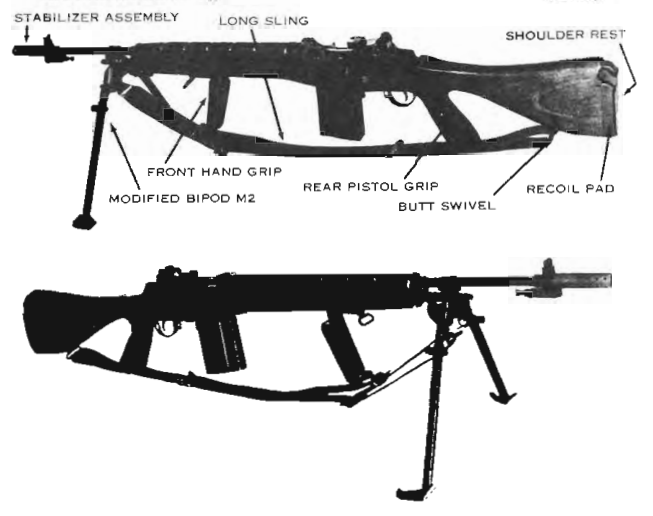

The M15 worked, but after some experimenting, both the Army and Marine Corps found that the M14 with a bipod was just as good as the M15. This caused the military to abandon the M15 and its heavy barrel. In its place, they developed the M14E2.

The M14E2 became the M14A1 and was a radical departure from the M14. The gun wore a wood stock, but the weapon used a rear vertical pistol grip and a folding forward grip for greater stability. Like the M15, the gun got a bipod and a hinged stock. Across the top, a polymer handguard helped keep things cool during full auto fire.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The M14A1 still had some serious problems as a squad support weapon. It was difficult to control, and while improved compared to the M14, the M14A1 was still a rough ride. The BAR had six more pounds on the gun, and that helped eat up recoil. Additionally, the BAR had a slower firing rate and was more controllable. The M14A1 spit 750 rounds per minute and was a bucking bronco.

This killed the idea of the M14 and M15 in use as an automatic rifle. The M60 was the general-purpose machine gun of the era. In the midst of Vietnam, the full auto M16 became an ad-hoc squad support weapon. Later, while waiting for the M249 the USMC even produced bipod-equipped M16s to play a familiar role.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

So there was an M15, but it never got its chance to shine.