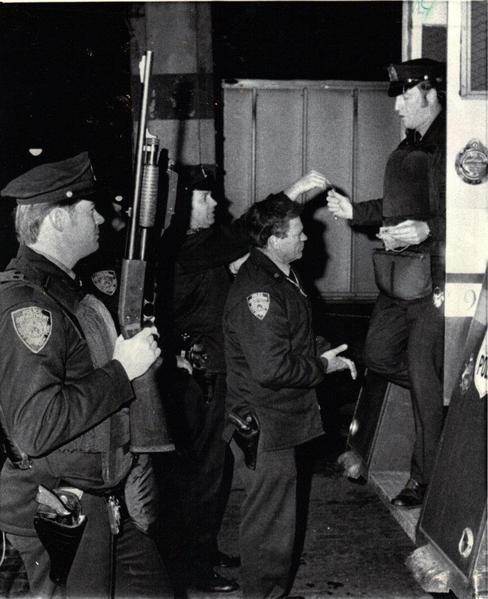

The NYPD’s Stakeout Unit was formed during a tumultuous time in the late 1960s in New York City where the risk and danger of violent robberies was a very real concern. Small cash businesses like convenience stores, mom-and-pop grocery stores, Western Union offices, motels, etc. were often easy targets that violent criminals liked to exploit—sometimes repeatedly.

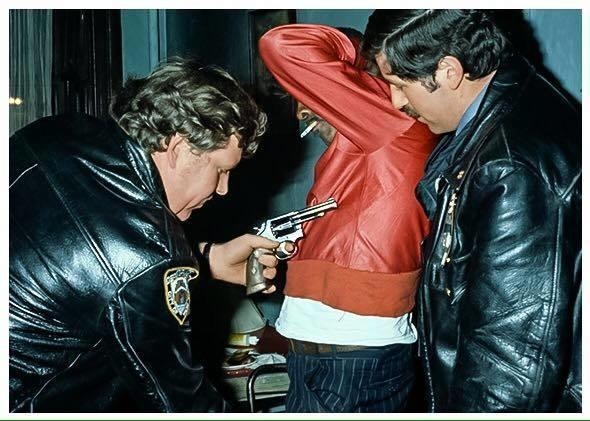

The NYPD SOU (Stakeout Unit) would screen through incident reports of these at-risk businesses and then choose to intervene in some of the riskier profiles. SOU officers would visit these businesses in person and evaluate them. If deemed necessary, a team of SOU officers would remain during business hours and conceal themselves on the premises. These teams kept watch over customers and the business ready for anything to happen. The minute any sign of a violent robbery materialized, these well armed officers were ready to jump into action and stop it by any means necessary. Due to the fact that the SOU’s direct assignment was confrontation with armed felons, total control of the situation was critical to the SOU in order to avoid situations that deteriorated and began involving innocent bystanders or hostages. It was imperative to never leave that up to chance. For this reason, the officers in the SOU teams were typically better acquainted with their personal weapons and tactics than regular beat cops of the era.

HANDGUNS

From the years spanning 1928 through 1993, the standard issue handgun for New York Police Department Officers was a six shot, fixed sight, four inch barreled, double action revolver chambered in .38 Special. According to Jim Cirillo, a well known member of the SOU, police cadets had the choice to purchase either a Smith and Wesson “Military And Police” (known as the Model 10 after the year 1957) or a Colt “Official Police” revolver upon completion of the police academy.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Cirillo himself was known to carry two Model 10s, a standard and a bull barreled model, as he preferred the smoothness of Smith and Wesson action as opposed to the Colt’s. Each SOU officer was required to carry either of these official service sidearms while on stakeout assignment. Given the time period, context, and mission requirements for these officers, they actually typically carried more than one handgun. The tongue-in-cheek term, “New York Reload” coined by Mr. Massad Ayoob, was attributed to the fact that when he once asked Cirillo about his preferred revolver reloading technique, Cirillo stated that he didn’t worry too much about it—he just switched to different guns as he needed them.

Cirillo personally tuned both of his service revolvers and he had an amateur gunsmith (another SOU teammate) help modify the factory sights to make them more useful and quicker on the target. The NYPD regulation cartridge at the time was a .38 Special loaded with a lead round nose 158 grain bullet that had a muzzle velocity of 700 fps (feet per second) which was held with disdain by Cirillo. He thought it to be inadequate and instead opted to load his revolvers with custom loaded .38 Special Super-Vel cartridges with a 110 grain hollow point bullet traveling at 1,125 fps. In spite of his extensive hands-on experiences with the terminal effects of .38 Special ammunition, his choice of alternative cartridges was something that caused a sore spot with some of his department superiors. It wasn’t until the year 1972 that the NYPD started issuing service cartridges with a semi-wadcutter bullet profile and finally replaced the older LRN (lead round nose) bullet. The SOU was the first police unit to field this ammunition and Cirillo did consider it to be a step in the right direction.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

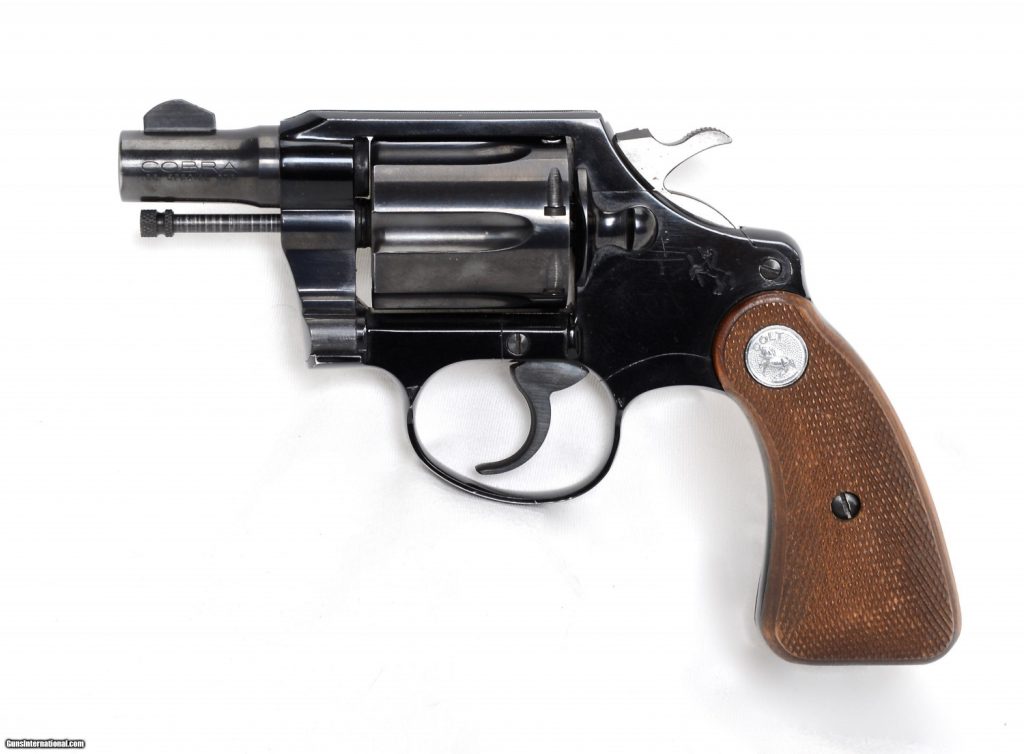

Backing those two Smith and Wesson service revolvers was a six shot snub nosed Colt Cobra revolver which he preferred over the S&W J-frame due to the fact that the Colt holds an extra cartridge. Both Model 10 service revolvers were carried openly on belt holsters on either side of his hips “like a cowboy.” The Colt Cobra sat in a front pocket and had a shroud over the exposed hammer to avoid any snagging on the draw. Cirillo had a preference for loading this particular revolver with wadcutter cartridges, as he believed they offered better terminal performance from shorter barrels. For some time Cirillo also carried a Walther PPK blowback semi auto sub compact pistol chambered in .32 Auto in a “crotch holster” (sic) as a measure of last resort. He claims it never saw much action besides the time he shot a rat at a gun range. Upon the realization of this Walther’s collector value, he cleaned it up and sold it.

image credit: Gunsamerica

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Though all SOU officers were required to carry their official service revolver on duty, they had no such rules against carrying multiple handguns of other types. In fact, many SOU officers carried alternatives such as Browning Hi-Powers or various types of 1911s. These officers’ weapons had to be approved by Bill Allard who was the unit’s T&E officer (and Cirillo’s main partner). Allard held the power to approve or deny gear.

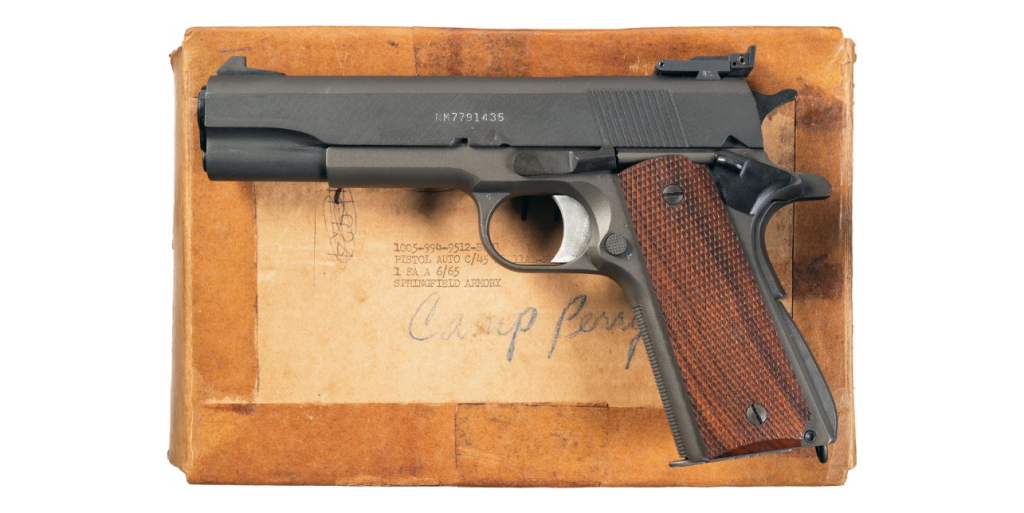

Allard himself always took his personal Camp Perry built Colt National Match .45 Auto 1911 pistol to every stakeout mission he was part of. The National Match pistol is a customization of a military 1911 pistol by military gunsmiths who modified them with target sights and match barrels in order to wring out match grade accuracy for use in accuracy intensive Camp Perry pistol matches. Allard claimed that he personally won one such high level pistol match with his particular NM 1911 pistol. That specific gun was one of three that he personally evaluated at Camp Perry on the fifty yard line and then purchased in 1967—the last year these handguns were available for sale. Allard carried the pistol the same way it left the gunsmith’s bench and only lubricated it and maintained it as necessary. He carried his Colt National Match 1911 pistol with three extra magazines, all loaded with 200 grain .45 Auto Norma hollow points—these were either his own handloads or factory ammunition. Concerning handgun ammunition choices, Allard and Cirillo had differing opinions; Cirillo preferred a quick moving .38 caliber bullet, and Allard preferred a slower but heavier .45 caliber bullet because he thought these offered better penetration potential in order to punch through bone and reach fight stopping vital organs. With regards to the mandatory NYPD issue service revolver, Allard preferred the Smith and Wesson Model 10 with a bull barrel as he thought it had “fantastic” overall balance. His backup snub nosed revolver was a Colt Detective Special for no other reason than that’s what the police department had available at the time of his purchase.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

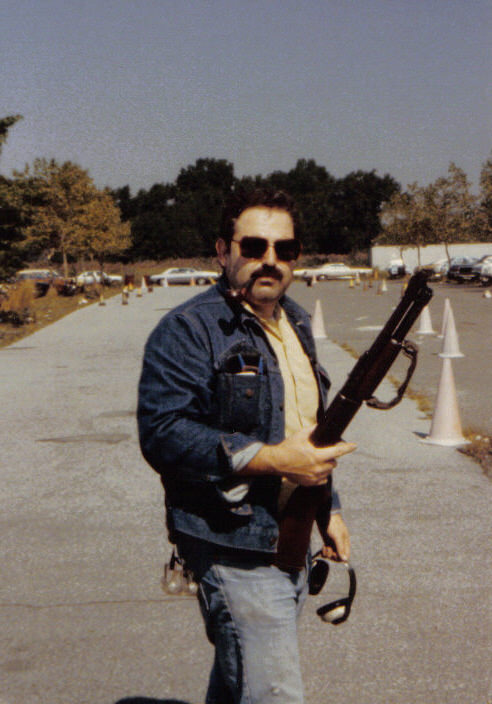

LONG GUNS

The SOU used both twelve gauge pump action shotguns and lightweight M1 Carbines to great effect as workhorses on stakeout missions. It should be noted that in addition to shotguns or M1 Carbines the SOU also used the Smith and Wesson Model 76 sub machine gun—a clone of the famous “Swedish K” SMG, but according to Cirillo these guns were “unreliable pieces of shit.”

As far as American pump action shotguns are concerned, the Ithaca Model 37 shotgun was one of the most prominent 20th century shotgun designs that both fell flying game and interdicted criminals. Designed by John Moses Browning, this shotgun was possibly the world’s first ambidextrous pump action shotgun; due to its unique design, shotshells were both ejected and loaded from the bottom of its receiver. The left and right sides of this shotgun’s receiver are slick. Like some of Browning’s other shotgun designs, the Ithaca Model 37 has no trigger disconnector meaning that a shooter can fire all loaded shotshells continuously by cycling the action while simultaneously keeping the trigger depressed. Along with many other police departments during this time period, the Ithaca Model 37 was the standard issue for the NYPD as well. NYPD shotguns had twenty inch barrels and four round tubular magazines, which allowed the officers to carry up to five shotgun cartridges in the gun at a time. Cirillo mentions, “We had full length, and we had cut-downs—we loved the cut-downs because we were in tight quarters in some of the places we were hidden. We cut ‘em right down to the magazine tube, and then we welded a lanyard holder, because the muzzle was right there where you ended up pumping. So we had these nylon or canvas heavy webbing straps attached to ferrules so that you put your hand in there, you could keep your hand open and just slide it in like a karate chop, and you could fire this gun as fast as you could pull the trigger.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Though the twelve gauge buckshot ammunition available in the late 1960s and early 1970s was unsophisticated in comparison to modern tactical buckshot, the SOU being an adaptable unit still used shotguns to their advantage. Allard mentioned having a rule where buckshot was to be fired within distances of up to fifteen yards, and for anything past that, one ounce slugs were preferred. This was something he did to account for the possible spread of errant pellets. According to Cirillo, the SOP (standard operating procedure) for nighttime stakeout duty was to load a shotgun with slugs last in order to shoot them first inside a store where overhead lighting could aid in better aiming. They reasoned that if the use of force encounter spilled out onto the streets, they could then use buckshot to send a pattern to fleeing suspects or getaway vehicles. The daytime stakeout SOP for shotgun loading was the complete opposite—to send a column of shot against armed robbers inside the confines of the store and use slugs once the incident moved onto the daytime streets to mitigate pellet spread (as there would be more bystanders on daytime streets). SOU officers also briefly fielded sawn-off side-by-side shotguns favored by detectives of this time period. They did not last long on stakeout duty as SOU officers thought the low shotshell capacity to be a hindrance.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The M1 Carbine is a light weight, magazine fed semi automatic rifle designed on the eve of the Second World War and was issued to American troops who needed a weapon more capable than a handgun but did not need an infantry rifle or heavy sub machine gun. It was intended for men who manned artillery guns or carried communications equipment, but its light weight, compact size, and relatively high capacity (compared to standard infantry rifles of the day) also lent itself well for unconventional duties. It saw service up through the jungles of Vietnam until the more modern CAR-15 type rifle eventually superseded it. .30 Carbine ammunition was designed with a straight walled rimless casing that is reminiscent of a .357 Magnum casing without its rim. Projectiles were shaped like other handgun bullets as opposed to longer and heavier full size .30 caliber sptizer rifle bullets. Out of their eighteen inch barrels, these carbines typically pushed those 110 grain FMJ bullets at just a hair under 2000 fps. According to Cirillo, the M1 Carbine was an all around SOU favorite. He recounted, “They were great for stakeouts because we were in tight quarters, behind walls and such. We hand full-length ones and some that were cut down. When we confiscated an M1 Carbine on a case, it went to the range and our gunsmith would cut down the barrel to just about 12 inches and put on a folding stock and pistol grip. You know what? The carbine was one of our best stoppers. Our gunsmith was real good; he was able to fix those magazines so they reliably fed hollow point 110 grain Winchester ammo, an expanding bullet. You figure you’re shooting a hollow point bullet that’s going between 1,800 and 1,900 feet per second. That velocity gave us good hydrostatic shock. When that bullet opened up and folded back, it was superior to our handgun for sure. It was fast to shoot, light recoil, and you had 15 rounds. It turned out that anybody that was hit with it, even if they weren’t hit in the vitals, got dropped. We had one guy [who] (sic) was hit in the thigh, and he ran outside, his leg broke, and he fell. Evidently the tissue was so torn up, or the bone might have been fragmented, or touched; his leg broke, he had a compound fracture, he went down on the ground.” All M1 Carbines owned by the NYPD at the time were semi automatic only.

THOUGHTS

These days, hyper-reliable pistols with magazines that hold nearly twenty cartridges spoil the gun owning public. Moreover, the proliferation of slide mounted electronic red dot sights on duty and carry pistols has helped the modern shooter to wring out even more capability from their handguns. If one compares and contrasts the pistol found in the holster of the contemporary “switched on” shooter against those in Cirillo’s or Allard’s holster, it can certainly evoke a feeling of respect and appreciation for the skill at arms those officers and their SOU brethren had. These SOU officer all developed a general sense of what to expect on a stakeouts in addition to a fundamental understanding of what they could accomplish or could not accomplish with their guns and gear. Logically, they implemented creative adaptations to keep any unfair advantage. An obvious example is the fact that practically all SOU officers carried more than one handgun as switching to another sidearm would always be quicker than reloading any of their relatively low capacity weapons. Police shooting standards in those days also placed a very high premium on accuracy and the understanding that a revolver held only six rounds—making every shot count was how business was conducted. The NYPD SOU was active from 1968 through 1973. With the exception of the M1 Carbine (frankly one of their most “modern” weapons), the designs of the pistols and shotguns fielded by SOU officers had not fundamentally changed since the turn of the 20th century when many of these firearms were first introduced and developed. M&P (or Model 10) revolvers and the .38 Special cartridges were a product of the turn of the century, as the original Model 1899 Hand Ejector revolver isn’t that different from its descendants. The .38 Special cartridge in fact dates back to 1898 and was originally loaded with black powder. The same is true of Bill Allard’s National Match 1911 pistol—other than the target sights and extra care from a gunsmith, Allard’s gun design had not changed since the year the US Military adopted Browning’s .45 Auto pistol, 1911. In the same vein, by the time the SOU was formed in 1968, Ithaca had already manufactured its one millionth Model 37 shotgun at its upstate New York factory.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

It wasn’t just that men like Allard and Cirillo were “gun nuts” that spent ample time shooting and tinkering outside of their job duties. While both considered their frequent participation in shooting matches to be crucial for their development as shooters, it also wasn’t just that either. The reality is that the men of the SOU were able to prevail during these armed violent encounters due to their intimate familiarity with interpersonal violence. It was a phenomenon they experienced almost quite literally every time they went to work. As a result, the comfort and familiarity of knowing themselves in the heat of danger allowed these men to remain cool and collected so that thinking with a gun in their hand was second nature allowing them to solve the task at hand.

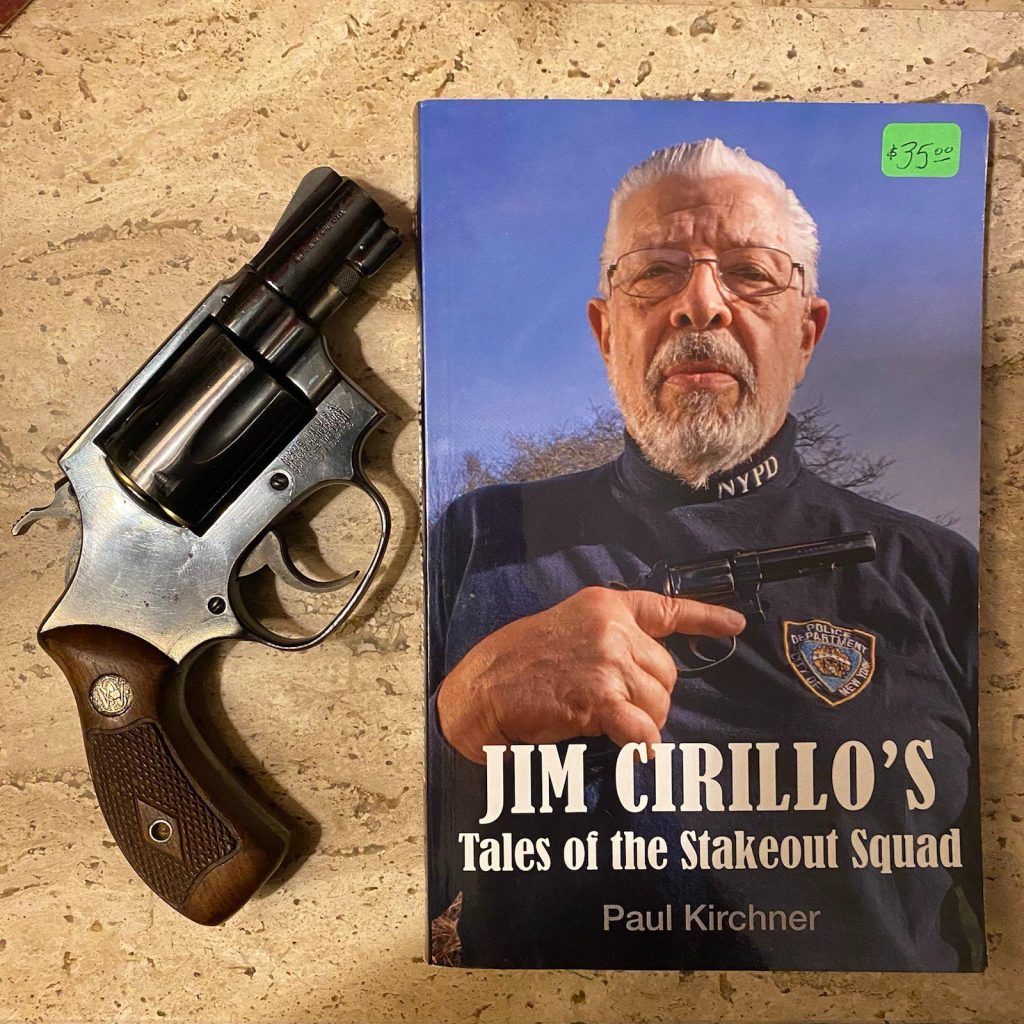

Author’s Note: Special thanks to CM for loaning me his copy of “Tales Of The Stakeout Squad” by Paul Kirchner. This book is out of print and relatively expensive to purchase nowadays. Additional gratitude goes toward DB for his explanation of background context to policing tactics of the era.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below