What if I told you that you could suppress a firearm without the need for a suppressor? You can actually muffle the sound of a gunshot by using a specific ammunition design. You are essentially silencing the gun with the ammunition itself. How exactly does silent ammo work? Did anyone actually use it? Is it effective? Today we’ll answer all those questions and more.

Digging Into Silent Ammo

How Does Silent Ammo Work?

Silent ammo is so simple and fascinating that it’s impressive it isn’t more common. If the NFA didn’t exist, I bet we’d see these cartridges flourish for various hunting purposes. The idea is simple: you must create a seal between the burning propellant and the projectile. There have been a few ways to accomplish this.

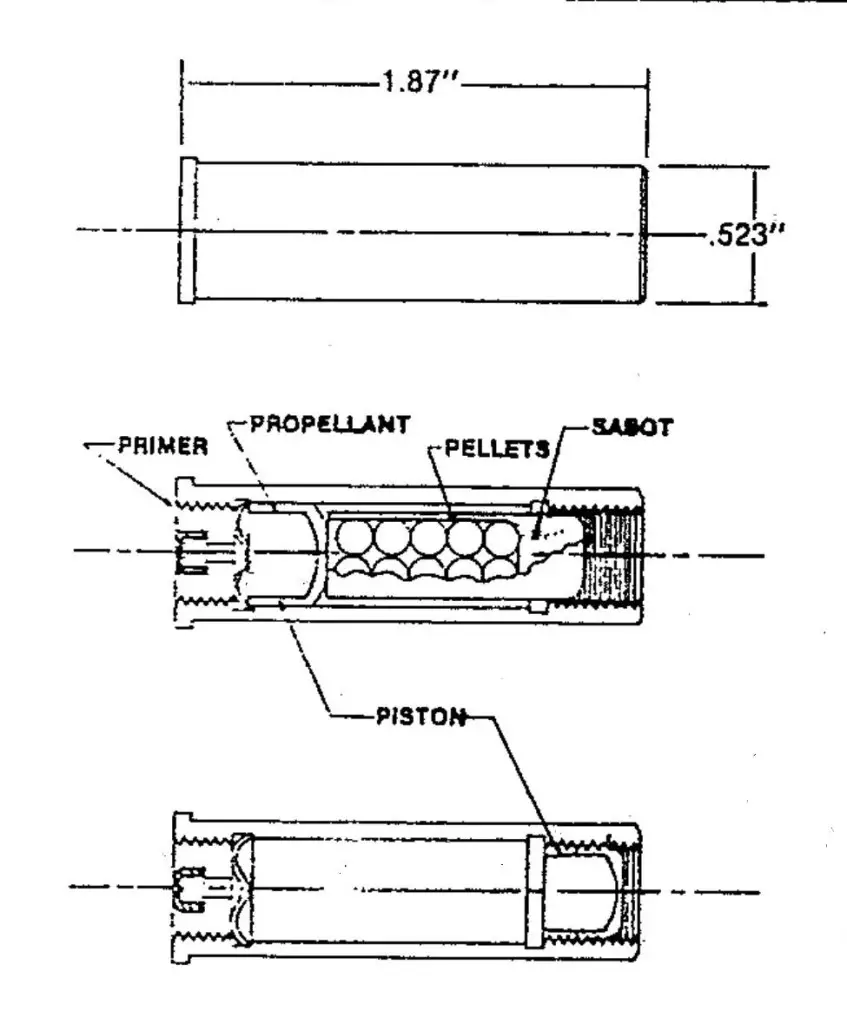

The most common method places a captive piston between the propellant and the projectile. When the primer ignites the cartridge, it drives the captive piston forward. The piston strikes the projectile and propels it down the barrel. However, the piston is designed to jam or “seat” at the neck of the cartridge case, acting as a gas seal that prevents the explosion of gas from ever leaving the casing. Since the gas is trapped, there is no muzzle blast and, therefore, very little noise.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Another option is a gas-sealed actuator. In some examples, the cartridge uses what is essentially a specialized metal diaphragm or aluminum foil. When the round is fired, the powder charge fills this diaphragm with gas, almost like a balloon, which then presses on the projectile and propels it forward. It is a very similar concept to the captive piston, just using a flexible actuator instead of a solid piston.

While there is likely a third method used in an obscure prototype somewhere, these two remain the primary ways to achieve “internally suppressed” ammunition. The captive piston is by far the most popular and successful of the two.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Who Used Silent Ammo?

The two main users of silent ammunition have been the United States and Russia. Unsurprisingly, the Russians made the most extensive use of the technology, while China has utilized it in a more limited capacity. America experimented with the concept during the Vietnam War but quickly moved on to more traditional suppression methods.

The Russians are the real sticklers for silent ammunition, producing numerous firearms specifically chambered for these oddball cartridges. While the Chinese made a silent dart gun for applying tranquilizers, we’ll focus on the lethal designs. The United States briefly explored silent rifle, pistol, and shotgun rounds, but never adopted them on a large scale.

The Russian Option

The Russians were big on this trend. Perhaps the clandestine nature of Soviet-era special operations made them prefer a quieter, less bulky option than a standard suppressed pistol. They stuck to the captive piston design for their silent ammo types.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

One of the first was the S4M, a highly secretive double-barrel derringer that fired 7.62 projectiles. This pistol was designed to fire a cartridge that would leave investigators convinced an AK-47 had been used from a distance, rather than a point-blank assassination weapon.

The S4M led to the MSP Groza silent pistol, another derringer design that fired a less powerful 7.62 cartridge with a much shorter case. These two double-barrel pistols eventually gave way to a semi-auto design called the PSS. This gun fired the SP4 cartridge and held six rounds. It used a unique design with a fixed barrel but a floating chamber to assist in cycling the action.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

They even reverted back to revolvers with the OTs-38, which uses the same SP4 cartridge with a moon clip. The revolver presents a simpler, more reliable mechanical option than the complicated semi-auto PSS.

The American Options

The blessings of American innovation allowed the United States to test multiple silent cartridges. The most prominent was the QSPR (Quiet Special Purpose Revolver). A product of the AAI Corporation, it was made specifically for Tunnel Rats in Vietnam. This was a Smith & Wesson Model 29 .44 Magnum revolver with the barrel trimmed to less than an inch.

The gun used captive piston ammo but was loaded with shot pellets. The cartridges resembled short .410 shells, each holding 15 tungsten-alloy pellets made from a material called Mallory. This tungsten alloy maximized density and close-range energy. The effective range was about 30 feet. An after-action report from an Army Ranger patrol mentions using the QSPR to kill an enemy combatant during a patrol.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

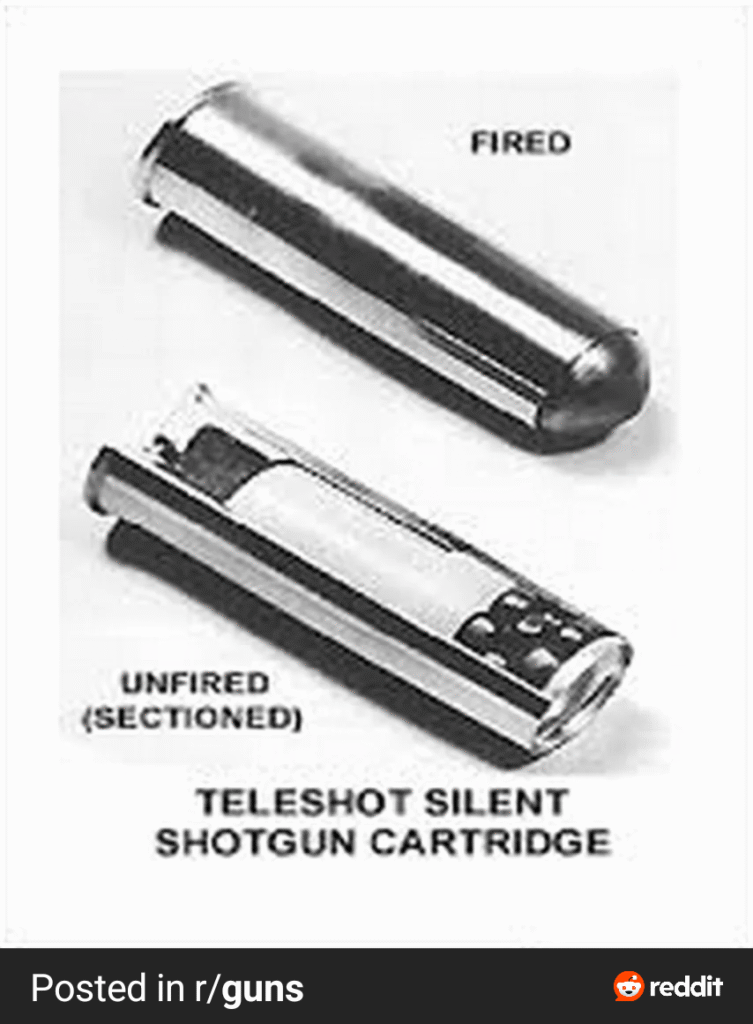

Beyond that, AAI produced a silent 12-gauge cartridge. This shell used a metal diaphragm gas actuator to propel 12 rounds of No. 4 buckshot from a standard pump-action shotgun. The cartridge was entirely metal. According to historian Kevin Dockery, the shell was not completely silent, but it made the weapon very hard to hear and effectively unnoticeable in a combat environment.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

AAI also developed the DBCATA system, which used similar technology to launch silent 40mm grenades. Information on this system is limited, but it was apparently extremely expensive to produce and was eventually scrapped.

Silent Ammo Today

The Russians seem to be the only people still fielding these weapons. Like many Russian designs, they pop up in conflicts around the world, including Ukraine and Syria. Beyond that, there isn’t much modern experimentation with the concept. The range is severely limited, and the firearms required to cycle these rounds reliably are difficult to engineer.

Today, suppressors are cheaper, more effective, and easier to field than a specialized gun with proprietary ammo. While the concept is interesting, it has very few modern military applications. Furthermore, thanks to the NFA, each individual cartridge would likely be legally classified as a “suppressor,” making the cost and paperwork a nightmare for civilians. Still, it remains a fascinating subcategory of ammunition that never quite got its time in the sun.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below