Which optic should you mount on your carbine?

“tHe 1 U WilL TraIN WiTh!” -Unhelpful Internet Keyboard Warrior/Commentator, paraphrased

Navigating the modern optical types, and why you might put them onto a carbine, is one of the most repeatedly voiced questions in this industry. Second perhaps only to, “Is this a good handgun for personal protection?”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Building what the US Army is now calling ‘Fire Control’ into your rifle’s equipment list is not a one size fits all proposition. You probably have a default base option if you’ve done this before. You probably also have a default recommendation if you’ve been asked this a few times. My personal default optic is a quality SFP LPVO. I don’t particularly care whose name is on it if it gives me a clean point of aim, but if pressed I’ll say SIG, Vortex, and Steiner.

My default recommendation, which differs from default personal choice, always tends towards, “Try a red dot first.” The $200-ish red dot game in 2022 is strong and the top tier models are still affordable in scale. If the response is, “I’d really like a LPVO.” well then get an LPVO, you can always change it later. Optics are becoming the pricier cousin of holsters, you start to collect them as you try different things. Slower than holsters true due to the price and higher likelihood you find something earlier in the search that you like, but I still have a larger pile of optics than rifles.

One of the most problematic selections you have to make as the shooter/operator/10 level user is defining your intended role and the effective range of the firearm. If you’re an Agency, the use role is probably officially defined. We aren’t building and saying its effective range, we are defining your effective range.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Is this a 3-Gun rifle? A precision rifle? A CQB/Home protection gun? A duty rifle that will carry legal defensive use/use of force implications? Is it meant to cover down on any or all of those roles? Is your rifle a specialist or an all purpose gun?

In short…

What do you need your rifle to do best, fastest, and first?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

These aren’t always easy questions. The reason they aren’t easy is the rifle you’re setting up is likely very capable of serving many of the listed roles. You see no reason not to cover all of the possible roles that you can, especially if its as simple as selecting an optic.

For the most part, if done properly with some practical training to back it, it is that simple. The difference between piss poor performance and passable proficiency is a far shorter time period than people think, but it isn’t a 0:00 time investiture and it cannot be substituted with equipment purchase.

Enough on training, back to selecting an optic.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After defining what you need your rifle to do best, fastest, and first, you get into the list of what would you like your rifle to do in addition to what you need it to do. Your optics are your most influential addition for exploiting your rifle’s full capabilities.

The trouble with choice (and tribbles)

Selection of an optic is not helped by the fact that every optic manufacturer is invested in telling you that their optic is the best optic for all the best reasons at being the best optically.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I’d love to say quality speaks for itself, but it doesn’t. Not always. Sometimes people just like the pretty pictures.

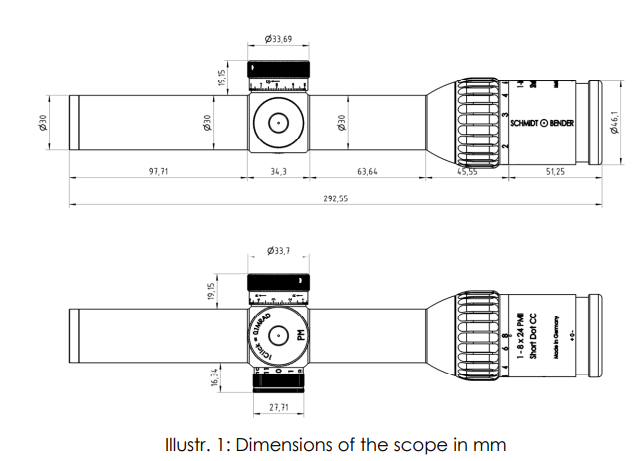

The S&B Short Dot that started the fighting gun LPVO path in earnest, after Gothic Serpent/Black Hawk Down, wasn’t commercially well known… at all. It was a combat grade optic by Schmidt & Bender, but they didn’t add the short-dot to a market that they were supplying with hunting scopes and they didn’t bother with the optic for a long time after fulfilling the contract and updates from Delta. Compounding that, the timeframe where the scope could’ve been sold was stymied by the Clinton AWB so there were far fewer commercially circulating rifles to even advertise towards. At the time not spending to talk about the Short Dot made sense, he market was small and the optic was niche and then the market was choked by legislation.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Quality on its own doesn’t speak at all, it merely exists. Users speak, so the quality item has to get into user hands and those users have to articulate the reasons they like it. A product also has to fulfill enough requirements for a purchaser to choose it. Those requirements will include cost per unit in most cases, especially for agency/group purchases on defined budgets.

Your heart may say KAC, HK, or FN, running a sweet Geissele trigger, with an ATACR or Razor III, and a MAWL and KIJI, and a Modlite/Cloud Defensive WML, and an offset RMR/ACRO P-2, a n d with your favorite rifle suppressor and…

So the heart says spend $10,000.00.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But your agency (or significant other) says keep it around $2,000 if you want to live. So prudence says something like a Z-15 with a PRO, or Duty, or P4Xi, a TLR RM2 light, add a moderate cost suppressor of quality. If there’s budget enough left over for the suppressor that is. Also you Chief or admin might still be on that ridiculous “too militant” schtick and you might have to contend with that.

So you can’t always get what you want. Is this ‘meets requirements’ rifle boasting the absurdly nice performance of the exquisite rifle and optical dream suite that you’d like?

No.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Will it probably serve your needs?

Yep.

Which is why we go back to asking what we need, then what we want, and finally where would our money be best spent?

You’ve got two choices for 2022

Red Dot or LPVO.

Realistically, based upon performance and needs, those are it. Two distinct optics for two distinct range roles.

Red Dot

Have a new rifle? Put a dot on it. Done. Right?

Which dot? That actually matters less and less the longer we let RDS technology develop and optimize. We are neatly topped up in quality red dot options from any of about a dozen places, and passable quality from triple that many. I recall days when the answer was an Aimpoint CompM2, EOTech 500 series, or a Bushnell TRS-25… and that was it. The market had nothing else to offer.

What does a red dot do?

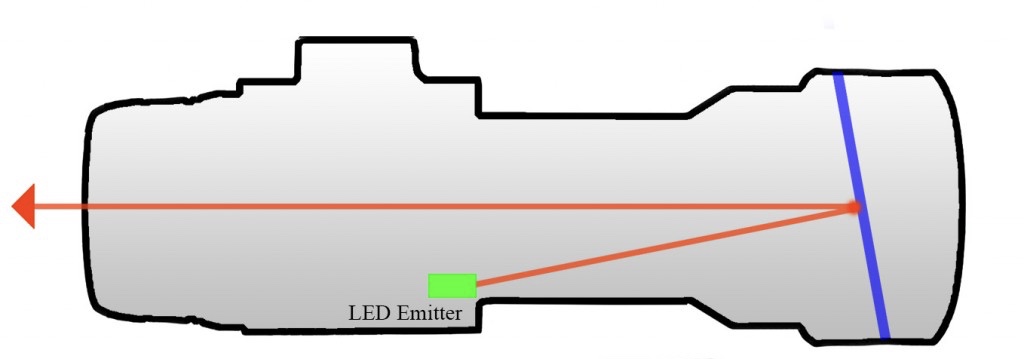

The red dot provides a precisely aligned aiming point that does not occlude the target. It does this with an LED (or a laser in the case of holographics) projected against a coated lens in alignment with the tube housing. Holographic emitter tech allows holosights to be more precise than the LED types, at the expensive of battery life, but those gains are marginal since the optic is on a 1.5-4 MOA accurate rifle to begin with.

Without getting into the extreme minutiae details of coatings, interrupted emission, parallax, etc. the red dot acts as a permanently aligned ‘iron sight’ on the rifle. This also removes interference with seeing all around the target. It offers a precise aiming point, and that point is much more indicative of any given rifle’s accuracy than a front sight post is. Recall that an AR front sight tends to be 13-18 MOA coverage and completely occludes everything below it. After about 150 yards the sight post appears larger than the target.

The red dot is aiming made easy, but not is not seeing made easy. Aid in seeing is why optics like the ACOG succeeded. That aid in seeing is now accomplished with the LPVOs or magnifiers too. Magnification has its place.

But the aid in aiming on a red dot remains both constant and forgiving of a users body position.

As goofy an image as that officer above is, it does illustrate a strength of the dot optics. That position, while horribly unstable, has a usable sight picture. All sorts of variations of oddball positions can still produce a useable sight picture with a red dot.

Sight alignment? The red dot sight is always aligned. Exempting a hard enough impact to move the optic, the optic will remain in alignment to the barrel and the flight path of the round. Variations on the flight path can be compensated for and trained into a red dot user, but comfortably generalizing a red dot allows for a point-of-aim = point-of-impact system. That is within a few inches of vertical spread, on almost any rifle, in any caliber, in any mount from a co-witnessed one to the tall UNITY types, with a 50yard/meter zero. It is a gross oversimplification, but its a field expedient one that hits that ‘close enough to be useable’ category. When in doubt, zero at 50 and drive on.

POA=POI: An AR-15 with a 50 yard zero, firing a typical 55gr round, with the optic 2.7″ above the bore (39mm, lower 1/3 type mounts).

The rifle would be hitting the target 2.7″ low with the muzzle touching the target. It would impact 1.25″ low at 25 yards. Going further, point of aim at 50 yards (zero). It would then strike the target about 1″ above the point of aim at 75 yards. It will reach the highest point of its flight at around 150 yards, striking at 2.3″ above the point of aim.

The total spread on my my quick example, put into a ballistic app, is 5″ of vertical travel from muzzle, to apex, to 280 yards where it is back inline with the muzzle 2.7″ below the point of aim.

Now if we additionally use the best practice of zeroing with the bottom edge of the dot, the red dot’s size works in our favor. A 2 MOA red dot at 75 yards is about 1.5″ of coverage, so a rounds impact is still within the dot’s coverage as it continues to rise. At 150 yards the dot is covering 3″ of space and the impact is only 2.3″ high, still covered inside of the dot. Until we reach that 200-300 yard (or meter) moderate range zone where the other environmental effects really start to come into play too, like wind and odd angles, the red dot remains a very simple and thus very easy to train aiming solution.

Magnify it?

Nearly as simple as the red dot itself, adding a magnifier to a rifle is a simple solution to the simple yet serious problem of being able to target identify and justify a shot. It also aids in things like zeroing even if you don’t keep the magnifier on the rifle permanently. Our eyes are really good (unless they aren’t, curse you age and genetics) at distinguishing details to about 50 yards. Which means the red dot is really good to about 50 yards, unassisted.

Past that distance we need an increasingly specific set of variables to justify taking a shot, magnifying our sight picture can give us that and strapping a magnifier of 3-6x in place behind the dot can be the simple solution that gives us enough information to make the shoot/no shoot decision.

Remember that a red dot on a rifle is not its range limiter, you and your eyeballs are. If it is a shot you are going to have to justify, you need the information to do that. This is why lights and optics are crucial pieces of equipment. A magnifier may make the difference between, “He was about 80 yards away and I saw something in his hands…” and “He was about 80 yards away and I saw the pistol in his hand. He raised it to shoot again so I fired and stopped him.”

Don’t think an 80 yard shot is “realistic”, do a rough wall to wall walking measurement of any major chain store. Wal-Mart, Home Depot, wherever really. There are public spaces, especially for law enforcement, where a long shot might be necessary.

Magnifiers are good options, understanding what they do for you gives you more options.

A red dot topped firearm with a room filling flashlight is a hard combination to top for home defense, or CQB, or any use space where 25 yards is the long shot. But rifles can grant effective close solutions without giving up anything, hence longer distance zeros and equipment to take advantage of them.

If you live in a serious, no exceptions, no ‘everywhere except this one spot’ world where a rifle only needs to hit something inside 50 yards very quickly, a dot on its own will cover you.

LPVO

Supreme rulers of the optical world for 2022.

Or it certainly feels that way online, doesn’t it? Unless you’re going for a specific niche or clone, if you aren’t running an LPVO now you’re well… not as cool as you could be if your scope did the zoomy thing instead of just the glowing thing.

Why is that?

The short answer is an LPVO is very good at what it does, and what it does is grant a user full range of effect on their rifles while not giving up that 1x CQB shooting. The LPVO has been instrumental in allowing shooters to actually take advantage of the fact their rifle is capable of fairly precise shots at 200, 300, even 500 yards.

A challenge to the user on how easy close distance shooting was makes the ACOG, as exceptional a sight as that is in totality, and other prism optics being increasingly relegated into niche or clone roles. Prism sights have steep adaptive curves for close distance shooting, especially above 3x magnification. A 4x and 1x joint sight picture between two eyes is difficult to reconcile, you can do it on an ACOG but it is still a disjointed information input. The Bindon Aiming Concept (BAC) was a good solution for its time, but we don’t need to do it anymore.

The LPVO vastly simplifies that information input, we can see 1x and 1x with only minor distortions instead of 1x/3-5x. We can reconcile that sight picture much more quickly, and if we need magnification we have as much or as little as we want for a shot on demand. The newest offerings are often 8x or 10x top level magnification. We’re topping patrol and service rifles with optics that meet or exceed what a sniper might have used in years past.

In 2022, with the LPVOs getting smaller, lighter, clearer, and increasingly more affordable, they are becoming a much more viable standard option for a carbine than we’ve ever had.

Things lost

You do lose two things going to an LPVO. The forgiving eye relief on a red dot and its small profile. Red dots today add very little weight to a rifle, especially the micro variants. Even the chonkiest of red dot sights is only about 12 oz in weight and maybe 6 inches of rail space taken.

An LPVO and mount are going to add about a pound and a half, no real way around that fact. They also have an eye box you have to get your eyeball into to find a sight picture.

They are more complicated and less durable. The far greater number of lenses, moving parts, and complexity make the LPVO a more susceptible optic than a red dot to problems. Less durable does not equate to “fragile” necessarily, but there is no way to make a magnifying scope body as durable to damage and environmental intrusion as a red dot is or an ACOG is. Not easily. Look at the MRO or the Aimpoint CompM5, then compare that to the VCOG. The VCOG being the only comparably durable LPVO. It takes a lot to harden a variable optic. I don’t know if the new Vortex XM157 is to the VCOG standard, I know the Tango 6T and Razor II/III’s in service are not. They’re durable but not to the level of the ACOGs or Red Dots. They can’t be, they are vastly different in construction complexity.

So the durability question gets balanced against the capability question. Do you need an optic waterproof to 66ft or do you need it to be able to be rained on and the resist mud? Those are levels of intrusion durability but one is less durable.

Things gained

There are perks, clearly. The magnification from 1-(up to)10x being the most obvious.

Additionally the LPVO is a solid state optic, its reticle is physical and not projected. This sight works with eyes that have issues with red dot flare, commonly astigmatism, they can also work well with more serious eye issues. This sight works if the battery is dead too. The reticle doesn’t go away if you forgot to swap your battery, you just might lose the bright dot or contrasting center of the reticle but not the whole reticle vanishing.

Reticle assistance is an assets the user gains too, reticles that help center quick shots at 1x and have more detail for aiding holdovers and hold offs for wind or moving targets are easy to add. The challenge is in scaling it properly to not be too much or too little to aid the shooter. It is easy to clutter a reticle.

Reticle design can vary wildly between the second and first focal plane scopes too, and a user can select which fits their need.

Second focal plane LPVOs are aided by their brighter sight pictures, easier and brighter illumination with better battery life, and simple reticle designs. It’s easiest to think of these optics like red dots with a variable magnifier included.

Front focal plane LPVOs can have much more complex and properly scaled Mil/Mil or MOA/MOA reticles that can aid shot placement at distance. The reticle scales with the target image so ranging, holds, and placement will always be to scale in a front focal optic build. The additional complexity and lenses in these do make for a darker sight picture and usually poorer illumination. The only true exception I have found to that thus far is the Razor III by Vortex, it has very nice illumination and glass.

FFP or SFP?

Click the question above for an explanation, already went down that path.

Which do you pick?

Try both. Find a friend, or a class, or a range where you can mess with both of them in proper context.

Proper context meaning one where it is properly mounted, eye relieved, batteries in, and everything able to be tried in its working format. A bunch of people get turned off certain gear because they aren’t handed it in a working condition to actually try instead of just stare at.

So, like most things, go shoot with them and find out.