I saw this article from Popular Mechanics last week and I’ve wanted to swing back to it for awhile. The problem was.. well.. Virginia was happening and we were busy.

But we’re back now so…

The U.S. Military Has a ‘Right to Repair’ Problem

What? You may be asking?

A ‘Right to Repair’. In short: who has the legal rights, through contract, to repair the equipment that soldiers are using.

Maintenance in the Military is a highly highly structured topic. Portions of that structure come from legal agreements with the companies who supply the equipment being used.

These agreements are a double edged sword.

On the one hand. Maintenance support directly from a company that built, say, an M1A2 Abrams tank or an M-ATV patrol vehicle mean that the folks who designed, built, and are looking to upgrade it are always in the loop working on it. That, instead of handing it off to a wide array of techs who all “grew up on” completely different systems and are relying on the accuracy of Technical Manuals (TMs).

The from concept to contract experience does give the company an edge in helping keep the fleet running. However, when certain maintenance tasks must be completed by a maintenance level the users don’t have access to in a timely manner, equipment gets deadlined.

Deadlined equipment isn’t helping complete missions and despite having thousands of people in uniform for the express purpose of maintenance, contracts restrict them from fixing their equipment at a closer level to the active mission than what the contract bound company can get their techs.

Companies make earnest efforts but you end up with situations where fixable pieces are kept deadlined by contract, not by ability. It is something that requires serious addressing as the military gets stuck with equipment lodged at various places in “shipping” for maintenance.

In short, the DoD needs to seriously address how it looks at contracts and add flexibility to help end users keep their equipment on mission at a higher rate. At the same time it needs to keep items that must unequivocally be maintained at the manufacturer level there to do so. They must, on demand, be able to deliver that maintenance. Improperly doing any of these will result in greater delays… hard nut to crack.

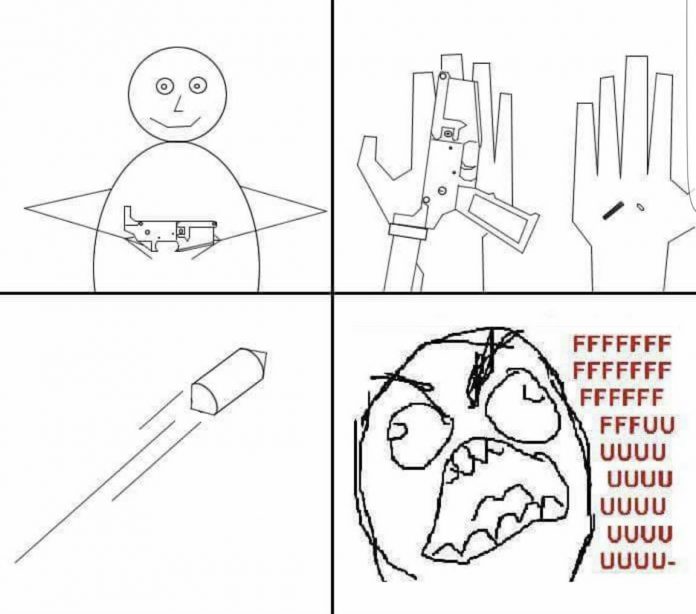

I’ve held a maintenance MOS. I spent 3 years looking at this problem from the inside and wondering, in many many instances, why? Why couldn’t competent folks following directions install a part as simple as a trigger? Contracts. The answer is weird contracts.

I see it from the manufacturer side too, though. Imagine, if you will, the number of ultra dumb customer service calls where a rep has to walk through plugging something in… now imagine that on a macro system running all the complex tests, parameters, and checks on a Predator Drone or the aiming components on a Paladin mobile artillery piece. Sometimes it is simply easier to do it yourself, in person.

This is a complex issue. But it’s one that is keeping a lot of equipment offline. The levels within the maintenance hierarchy are supposed to smooth this as much as possible by enabling the lowest levels, down to the end users, to keep their equipment running. There are breakdowns in this system, some are unfortunately contractual.