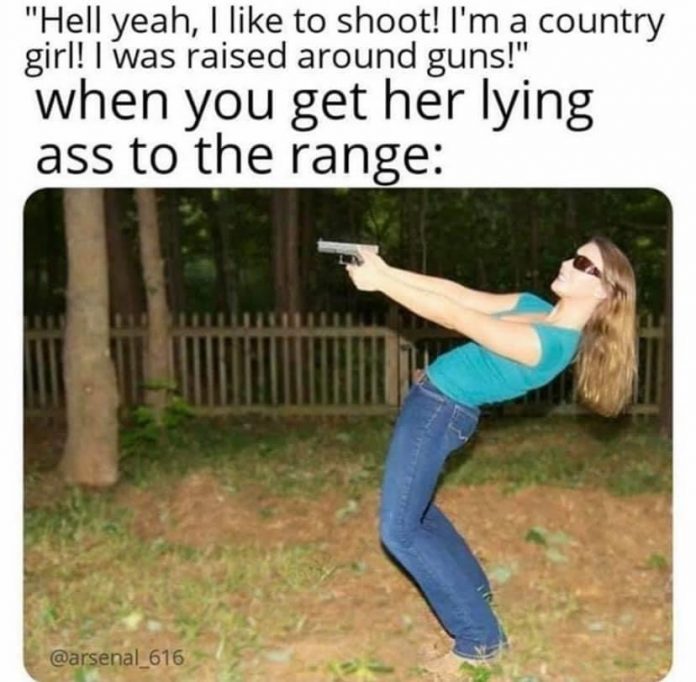

The title image meme struck home to me. The young lady dramatically exaggerating (but not by all that much) the very poor shooting posture that seems to plague firearm neophytes. But such poor form also runs rampant through the Dunning-Kruger afflicted ranks of the “I know how to shoot.. I grew up around guns my whole life.” crowds.

It struck me that this an effect similar to what we saw out of the military’s ‘Expert‘ ranks for rifle and pistol qualifications. The ‘Expertise Fallacy’ that we in the ranks of the US Military engendered (and in many cases still do) by granting the ‘Rifle Expert’ title to individuals who have shown an overall very basic degree of fundamental marksmanship in a highly structured setting that is geared towards high success rates… because success rates in a record book look good.

Henry of 9-Hole Reviews did a phenomenal job in the video at highlighting the topic, including visuals for scale.

What I realized, upon seeing the title meme, was that civilians have this fallacy too, but in a so much worse format because there is not an environmental control (IE: Basic Training) that really defines what ‘growing up around guns’ and ‘liking shooting’ are. There are no standards for ‘growing up around’ and ‘liking’.

I know men and women whose personal definition of ‘liking shooting’ is just being included on range trips and firing whatever it is everyone else brought. I know others who just like plinking with .22’s. I know still more who just like shooting their duty weapons at the annual qualification and occasionally with friends. More still just fire a few rounds for hunting preparation as they roll into the relevant season.

None of these folks are in the wrong for enjoying shooting how they choose to do so. This is not to shame anyone for how they choose their method of involvement or enjoyment of 2A benefits.

It is to highlight a parallel false expertise.

Or in this case the false competency/familiarity with firearms that most of these users do not have. Some of these people may have owned firearms for decades and are still at their novice stage in the discipline. That’s alright, some people just learn Mary had a Little Lamb and Chopsticks on the piano, not Mozzart, Bach, or Beethoven. The difference is the people who can only play Mary had a Little Lamb aren’t telling everyone how good they are at piano whenever music comes up… that isn’t as true of the firearm circles.

This is partly the origin of ‘The Fudd’, actually. Someone who on the actual table of expertise is still very low but who, in the immediate circle of onlookers and listeners, may be the most experience available. They also don’t recognize their limited knowledge and will expound beyond their experience. The same egotistical traits that lead to ‘Stolen Valor’ can manifest in a more minor form here with false expertise.

Now, this is far from universal within novice shooters, it just happens often. It is also very rare in niche experts like trap and skeet shooters. I don’t see many of them trying to rattle of CQB knowledge just because they’re fantastic at cracking clays, they’ll happily show you how to do that though. RIP to that money you were saving for some other project.. it’s now a nice O/U shotgun.

Ladies and gentlemen, shooting is a discipline. It is a sport, a life saving skill, a martial art.

Simply firing a gun is easy. Many people do that, sometimes not on purpose. Firing in a safe direction and getting pleasure out of it is only marginally more difficult. But shooting, being a proficient person with a weapon, is a developed set of knowledge and skills. That development covers understanding your equipment, what it is capable and incapable of, how to maintain it, how to use it safely, and how to maintain your safety too.

Many recreational plinkers are not shooters, they don’t know how to shoot. They may (hopefully) know how to safely handle a firearm and discharge it in a safe direction. Many will barely know (or do not know) how to load or unload the gun they are shooting, they have one person who does it for the group. They are as ‘proficient’ at shooting as they are at boating and water safety by stepping onto a pontoon boat with a drink. I bet they enjoy ‘boating’ as they cruise around the lake on a calm day at 3mph sipping a delicious summer beverage, and not driving the boat.

Ultimately, this is why hearing “I grew up around guns.” inspires no actual confidence in a person’s ability to safely shoot or handle a gun.

I’ve seen it too many times go awry. Overconfidence in lack of understanding and no awareness of their lack of understanding.

In the field of psychology, the Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability. It is related to the cognitive bias of illusory superiority and comes from the inability of people to recognize their lack of ability. Without the self-awareness of metacognition, people cannot objectively evaluate their competence or incompetence.[1]

As described by social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, the bias results from an internal illusion in people of low ability and from an external misperception in people of high ability; that is, “the miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others.”

The psychological phenomenon of illusory superiority was identified as a form of cognitive bias in Kruger and Dunning’s 1999 study, “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments”.[1] The identification derived from the cognitive bias evident in the criminal case of McArthur Wheeler, who, on April 19, 1995, robbed two banks while his face was covered with lemon juice, which he believed would make it invisible to the surveillance cameras. This belief was based on his misunderstanding of the chemical properties of lemon juice as an invisible ink.[2]

Other investigations of the phenomenon, such as “Why People Fail to Recognize Their Own Incompetence” (2003), indicate that much incorrect self-assessment of competence derives from the person’s ignorance of a given activity’s standards of performance.[3] Dunning and Kruger’s research also indicates that training in a task, such as solving a logic puzzle, increases people’s ability to accurately evaluate how good they are at it.[4]

In Self-insight: Roadblocks and Detours on the Path to Knowing Thyself (2005), Dunning described the Dunning–Kruger effect as “the anosognosia of everyday life”, referring to a neurological condition in which a disabled person either denies or seems unaware of his or her disability. He stated: “If you’re incompetent, you can’t know you’re incompetent … The skills you need to produce a right answer are exactly the skills you need to recognize what a right answer is.”[5][6]

In 2011, Dunning wrote about his observations that people with substantial, measurable deficits in their knowledge or expertise lack the ability to recognize those deficits and, therefore, despite potentially making error after error, tend to think they are performing competently when they are not: “In short, those who are incompetent, for lack of a better term, should have little insight into their incompetence—an assertion that has come to be known as the Dunning–Kruger effect”.[7] In 2014, Dunning and Helzer described how the Dunning–Kruger effect “suggests that poor performers are not in a position to recognize the shortcomings in their performance”.[8]

Now further research into Dunning-Kruger seems to suggest that people truly aren’t that blissfully ignorant, but the research is also fairly limited and is hard to accurately independently measure because measurements inherently defeat the effect depending on how they are taken. Note, when people are asked a basic question like, “Can you shoot?” the reactive answer of just about anyone who ‘enjoys shooting’ will be, “Yes!” but if that question is developed into detail a more accurate overall assessment will likely emerge commiserate to their skill set within the discipline. They may still be misinformed about their competence, but by being taken through a detailed process of assessing their competence people will gain a more accurate frame of reference than from the initial broad inquiry.

Dunning-Kruger is most likely to be seen in these quick ‘broad inquiry’ settings and the effect is most prominently seen in settings where cognitive engagement hasn’t occurred, not that it cannot occur. If given an evaluation that engages that cognitive reasoning, self assessment will be more accurate. D-K shows up strongest when no time is given toward ‘warming up’ that assessment process and a quick broad datapoint is taken.

IE: “Can you shoot?” a binary answer question that, even if taken with whatever extra data is offered from a person asked, could heavily show the D-K effect. But the more we ask assessing questions and details, the closer we will get to an accurate self assessment within reasonable margins of error.

It turns out people aren’t that stupid once you get them thinking. It’s getting them thinking in the first place. I bet if I surveyed in two different orders I would see different results because of it. If I opened with, “Can you shoot?” or, “Can you shoot well?” and then asked 10 questions in detail I would likely get a very D-K like data set off of that first question specifically, while if I end the survey with that same question I’m going to produce results more accurate to a reasonable self-assessment. Taking a snap visceral answer versus a reasoned one after thinking has been engaged.

[Sidenote: Surveys can also be used to guide a result this way, usually when a given taker wants a result instead of wanting data. Gun control surveys are an excellent example of this, properly framed even I would be shown as wanting more gun control even though I’m a ‘Machine Gun Vending Machine’ type of guy.]

“I grew up around guns.” Isn’t an assessment statement, it’s an identity one. It is also based on perspective and context.

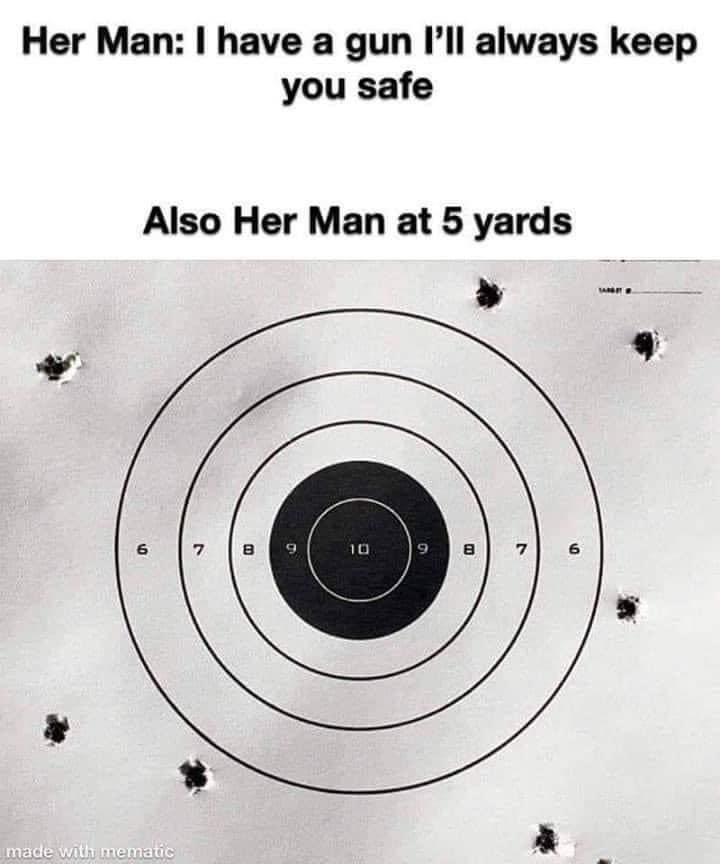

“I go shooting all the time.” might reference an average of 4-6 times a year during the good weather months. An average of once every 30-45 days. Where as, “I go shooting fairly regularly.” might equate to my personal 2-5 times per month during fair weather and dropping to 1 per month during inclimate weather.

I regularly attend professional training. On other occasions I am the trainer. But given the two statements without perspective which of us, me or hypothetical ‘all the timer’, shoot more? All The Timer, naturally, given no extra context.

Me shooting “fairly regularly” is 10,000 rounds, + or -, a year. Them shooting “all the time” might be 500. A ‘quick range trip’ in my book is 300 rounds. There ‘day at the range’ might be 50. Perspective is huge. How deep a self-eval gives somebody time to delve will influence perspective.

Nobody in the “I grew up around guns.” crowd is going to pretend to be a SEAL Team trigger puller… ok that’s not entirely true.

But the vast super majority would not rate their skills at SWAT or Special Operations level. They would, given little time to objectively self reflect, rate them positively. The more training someone has the more quickly and objectively they are going to rate themselves and with greater accuracy, even a passing familiarity and an objective thinking period will improve the assessments.

Why? Because standards become introduced. If there is not a standard people will make one up and probably not judge themselves below it.

So be forewarned, “I grew up around guns.” is not a statement of skill or competency. It is one of identity first and foremost. To assess competency we must put measurements in place.