[Ed: Dr. Faria originally published this December 16 on his website, Hacienda Publishing. His is an extraordinary story, standing for liberty throughout his career, carrying on a proud family commitment. Formatted for DRGO.]

I was born in Sancti Spiritus, Cuba in 1952. Sancti Spiritus and the surrounding area have been traditionally hot beds for revolution. The Escambray Mountains are in the vicinity, which rebels notoriously used for guerrilla warfare. That same year (1952) Fulgencio Batista carried out a successful coup d’état and became dictator. Although subsequently he was elected President, he was despised by the intelligentsia and not considered the legitimate head of the Cuban Republic.

At first, the common people were for him because he brought tranquility and prosperity to the island. But the following year in 1953, Fidel and Raul Castro began the revolution by attacking the military Moncada Barracks near Santiago de Cuba in Oriente province on July 26, 1953, a day that was immortalized as the name of their rebel movement. On March 13, 1957, a second group of rebels led a celebrated and more intrepid (although also suicidal) attack against the Presidential Palace in Havana in an attempt “to decapitate the government from the top” by killing Batista.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

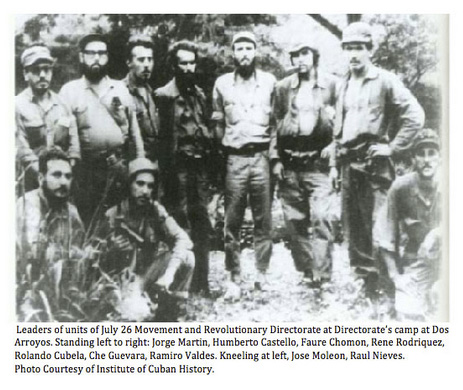

They failed and many rebels were annihilated, but the survivors, led by Faure Chomón and Rolando Cubela, formed a second movement. Because this group had began with students and recent graduates of the University of Havana, they called themselves the Student Revolutionary Directorate (RD). My parents joined the RD and became dirigentes of the 13 of March (RD) underground movement in Sancti Spiritus.

Following the Presidential Palace attack, my parents hid and protected the leader of the group, Chomón, for weeks in our home, while still planning and conducting underground activities from our kitchen. Even as a young child, I was aware of what was happening and feared for my parents’ lives. Nevertheless, my clandestine duty was to help entertain Chomón, who we code-named “Ricardito,” and who told me stories.

So there were two fronts waging war against Batista. Fidel’s group in the Sierra Maestra mountains included communists, such as Che Guevara and Raúl Castro, and fought desultory guerrilla warfare in that very isolated, rural and mountainous area of eastern Cuba. Fidel had charisma, lied to the press, and was helped to power by both the American and Cuban news media. All of this is narrated in detail in my 2002 book, Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

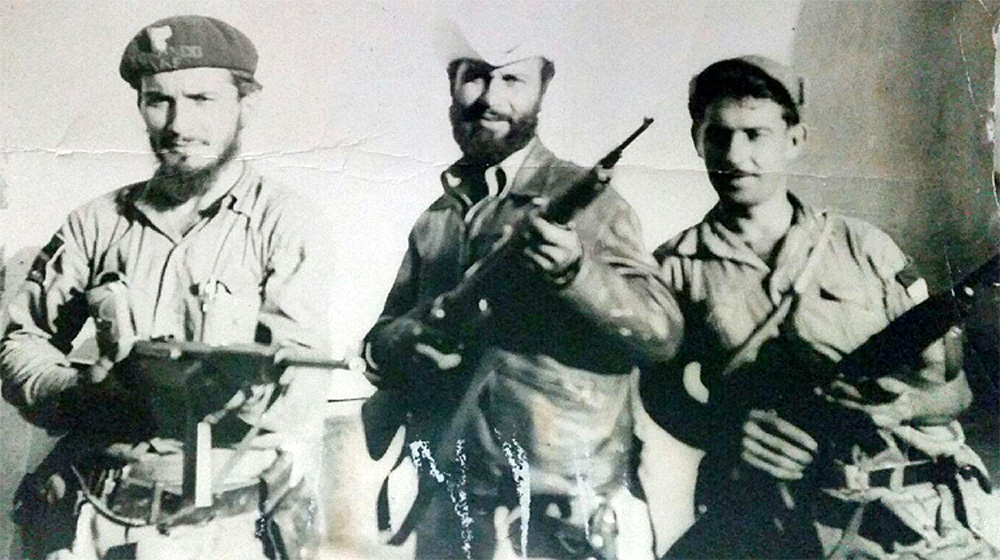

By contrast, the RD or 13 of March Movement, centered in Havana and Sancti Spiritus, used extensive underground and urban guerrilla tactics, fighting in major cities. No communists were allowed in this group. The RD also had a rural guerrilla front in the Escambray Mountains to which my uncle Julio Martínez (pictured center in photo above) served under Rolando Cubela, whom he called fearless.

My parents used to take arms and recruits to the rebels in the Escambray, as this battleground was close to our farm. Once we were halted at a check point, but when the military police learned it was my father, one of the three cardiologists in our town, they waved us to continue and did not search the vehicle. I remember hiding my toy guns under the seat of the car and fearing for our lives. We triumphed but soon it became obvious the nationalist revolution had been betrayed by a communist revolution.

Fidel’s charisma made him “maximum leader,” and the 26 of July Movement with communists in its ranks became the new Cuban government, and the Soviets were invited into the island. When Faure Chomón threatened to oppose Fidel and wanted the RD and the Cuban people to keep their firearms, Fidel refused. In a major speech he clamored, ¿Armas para que? Guns for What? There would be no more insurrections. Not only the members, but also the common people were disarmed.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Some RD leaders, such as Osvaldo Ramírez (pictured on right in photo, left), went back to the Escambray Mountains and led a powerful insurrection against the communist regime, from 1961 to 1965, but eventually Ramírez and his peasant rebel army were wiped out. They did not have enough arms and ammunition.

That same year, 1965, Rolando Cubela, who had been working with the CIA (Operation Mongoose), was arrested in Cuba for conspiring to assassinate Fidel. We were warned that the secret police was also on our tail, and my father decided we needed to flee the island. We did so on February 13, 1966. We “sailed” south to the Cayman Islands, and after a three-month Caribbean odyssey, which I as a 13-year old considered a great adventure, we legally entered the United States.

Later we were told that the Cuban secret police (G2) had learned of our escape and searched our homes and interrogated my mother. A small G2 plane searching for us crashed, killing the G2 officials in it and infuriating the regime. Some of my relatives were also interrogated and arrested.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I reached freedom in the US, became an American citizen, and was brought up and educated in the South. I completed my undergraduate studies at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, receiving my BS degree (Biology and Psychology) and graduating magna cum laude in 1973. I then attended the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, and was inducted into Alpha Omega Alpha Medical Honor Society (1975). I graduated with honors, receiving the Merck’s Manual Award for scholastic achievement, and earning my M.D. degree in 1977. I completed my neurosurgical residency at Emory University (1978–1983) in Atlanta, Georgia.

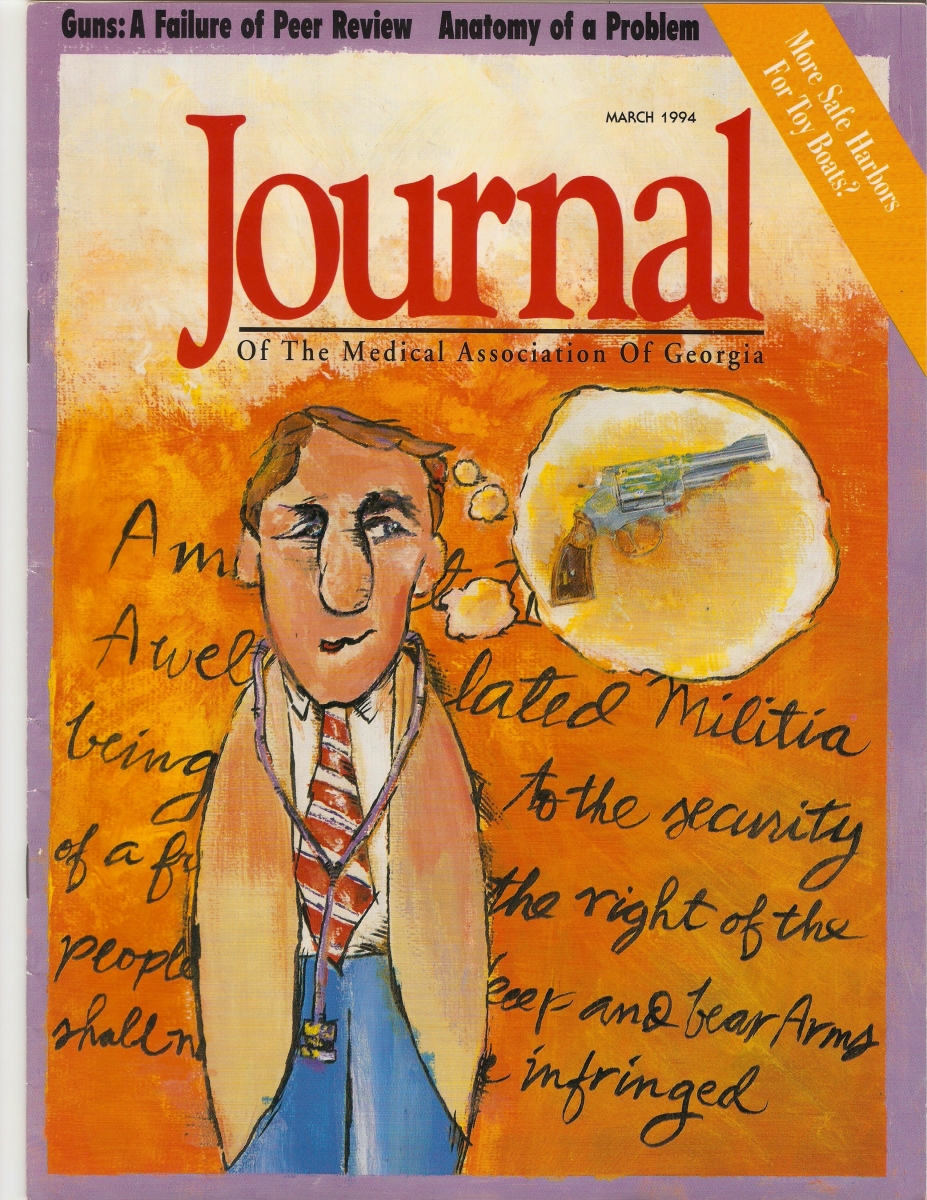

I became a clinical professor in neurosurgery in Macon and the editor of the Journal of the Medical Association of Georgia in Atlanta. At the time, the AMA, our “umbrella organization,” was conducting a public relation campaign against domestic violence, which led to a campaign against “gun violence.” This was deliberately linked to gun ownership and supposedly backed by the scientific “gun research” conducted by public health officials at the CDC and various schools of public health.

I began writing about gun rights as soon as I discovered, first hand, that the Medical Establishment (ME), headed by the AMA, and the Public Health Establishment (PHE), headed by the CDC, had a bias against gun rights and civilian gun ownership, and that the purpose of their “guns and violence research” had a hidden agenda — namely, to push for draconian gun control. Moreover, the related giant medical publishing empire at their disposal was bent on publishing one-sided medical propaganda masquerading as objective medical journalism.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I was horrified to learn that true science, medicine, and public health did not really enter the picture; but rather that politicized, result-oriented junk science with preordained conclusions was used as the vehicle for their gun prohibitionist propaganda. I was in a central position to learn about this since I had also been elected a Delegate to the Medical Association of Georgia (MAG) in the 1990s and was now the duly appointed editor of the state medical journal. In conjunction with a PR campaign against domestic violence and the “guns and violence” propaganda that was being promulgated, I was expected to toe the politically correct line that “gun violence was a public health issue” and that “guns are like viruses that must be eradicated” from civilian ownership.

I refused to comply and found myself in the middle of the storm, arguing that we as physicians, could be compassionate but also honest and had a duty to at least publish both sides of the gun control debate. In other words, that law-abiding gun owners not only had constitutional protection, but also that guns had beneficial aspects in self and family protection, which needed to be aired in debates and publications in medical journalism. As a result of my stand, I lost my position as editor of the state medical journal in 1995 — so much for the much-touted free exchange of ideas and academic freedom! I narrated the story of my travails at the Medical Association of Georgia in my book Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997).

What happened in Cuba via revolution, I see happening here in the U.S. via evolution. Batista allowed civilians to keep their firearms, but the guns had to be registered. After the triumph of the Cuban Revolution and consolidation of the communist regime, Fidel Castro had his “militia” go to the registry offices and using the registration lists go door-to-door confiscating all firearms from the people. In Cuba, registration led directly to gun confiscation.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Taking the lessons I learned first hand in Cuba regarding civilian disarmament and what I saw happening in my adoptive country—namely, the misuse of science for political propaganda—I felt the need to write a comprehensive book that would cover the entire field of gun rights as well as public health and gun control. America, Guns, and Freedom: A Journey Into Politics and the Public Health & Gun Control Movements (2019) is the result of my labors and I think it has accomplished that goal.

.

.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

— Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is a retired professor of Neurosurgery and Medical History at Mercer University School of Medicine. He founded Hacienda Publishing and is Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International. He served on the CDC’s Injury Research Grant Review Committee.