Revolvers Are Stupid Guns

Hear me out before you rage fire that email to me or my editor. This isn’t the first time I’m saying this nor will it be the last: revolvers are pistols with very low capacity, have triggers that are harder to master and require additional care and consideration to keep in working condition. When these guns fail, they can go down hard and become merely blunt instruments. Unless you take the time and effort to handload, their ammunition costs more too. Revolvers are so damn stupid when you think about it! I could go on and on about what a waste of money they are. In fact, these days, a box of .38 Special costs approximately $12 more than a box of 9mm at standard retail pricing. As another point, it is said that serious revolver shooters carry around toothbrushes in order to clean out the star in between higher round counts. And of course, they own a Lewis Lead Remover too.

The Joy and Pleasure of Revolvers

Revolvers are guns that have conceptually been around since the first quarter of the 19th century, and yet an early Colt revolver or a Pepperbox is nothing like a Smith and Wesson Model 66. That they have not fundamentally changed in nearly two centuries makes them fascinating. And when it comes to shot-for-shot satisfaction, revolvers are extremely seductive weapons.

It isn’t just their lines or sleek finishes. These are pistols of panache–heavy and archaic. I think the reason they draw me in the way they do comes from the fact that a revolver is technically more challenging to shoot, and nothing strikes dopamine receptors like when the target and timer show evidence of proficiency with these guns.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After all, with their fixed barrels, they can be extremely accurate. Perhaps this emotion comes from the same place in the heart where the satisfaction of knowing how to shift gears in a manual transmission also comes from. There is certainly a sense of appreciation for the craftsmanship and quality of American gunmaking of times past, when shop floors in Springfield or New Hartford (and other places) were full of expert smiths’ benches. Both their tools and their careful hands would carefully lay parts into a working weapon with a level of care and detail that would (and does) cost a premium today. There’s something certainly appealing from their analog nature–how one must load the charge holes in the cylinder and how the trigger pull actuates the entire gun. Shooting double action revolvers is pure pleasure.

Because the revolver’s trigger has to not only turn the cylinder but also cock the hammer, it has a long trigger pull path and usually a hefty pull weight with it. But I believe that mastering this trigger unlocks all of the other trigger styles as well. The similarity is obviously there when controlling a TDA (traditional double action) semi-auto trigger. Taking advantage of a single action or striker-fired trigger then feels like cheating. The revolver trigger also teaches you how to naturally ride the trigger reset and to forget anything about pinning the trigger–it’s a waste of time, especially on a double action revolver.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Classic .38 Caliber

I prefer using .38 Special (and .22 Long Rifle ammo in revolvers). Because I shoot these guns purely for pleasure, I eschew the added expense of shooting [.357] magnum rounds. The classic .38 Special loadings work just fine, be they 158 grain lead, jacketed or coated round. The 158-grain bullet has been the classic loading for generations and most .38 Special revolvers’ sights and barrels are optimized for this weight of projectile. Adding to that visceral and emotional appeal of shooting these revolving contraptions is that lead ammunition leaves gunsmoke and leaves a certain smell wafting about the shooting bay. (Of which, lead ammunition also fouls up bores and part of the extra care and concern involves removing lead deposits from the bore). In addition to the classic 158 grain bullet, the .38 Special 148 grain wadcutter and 130 grain FMJ rounds are great to shoot too. Wadcutters are extremely accurate and even more gentle on recoil as their powder charges are milder. My favorite 130 grain factory load from American Eagle is a great round too. I find it to be very accurate and it groups consistently across various revolvers. Its only downside is that it does not shoot to some wheelguns’ fixed sight point of aim, something to keep in mind. When it comes to handloads, my goal with revolver loads is to stay within the classic specifications for consistency’s sake. After all, I don’t want my loads to interrupt my shooting and the sights are already regulated that way.

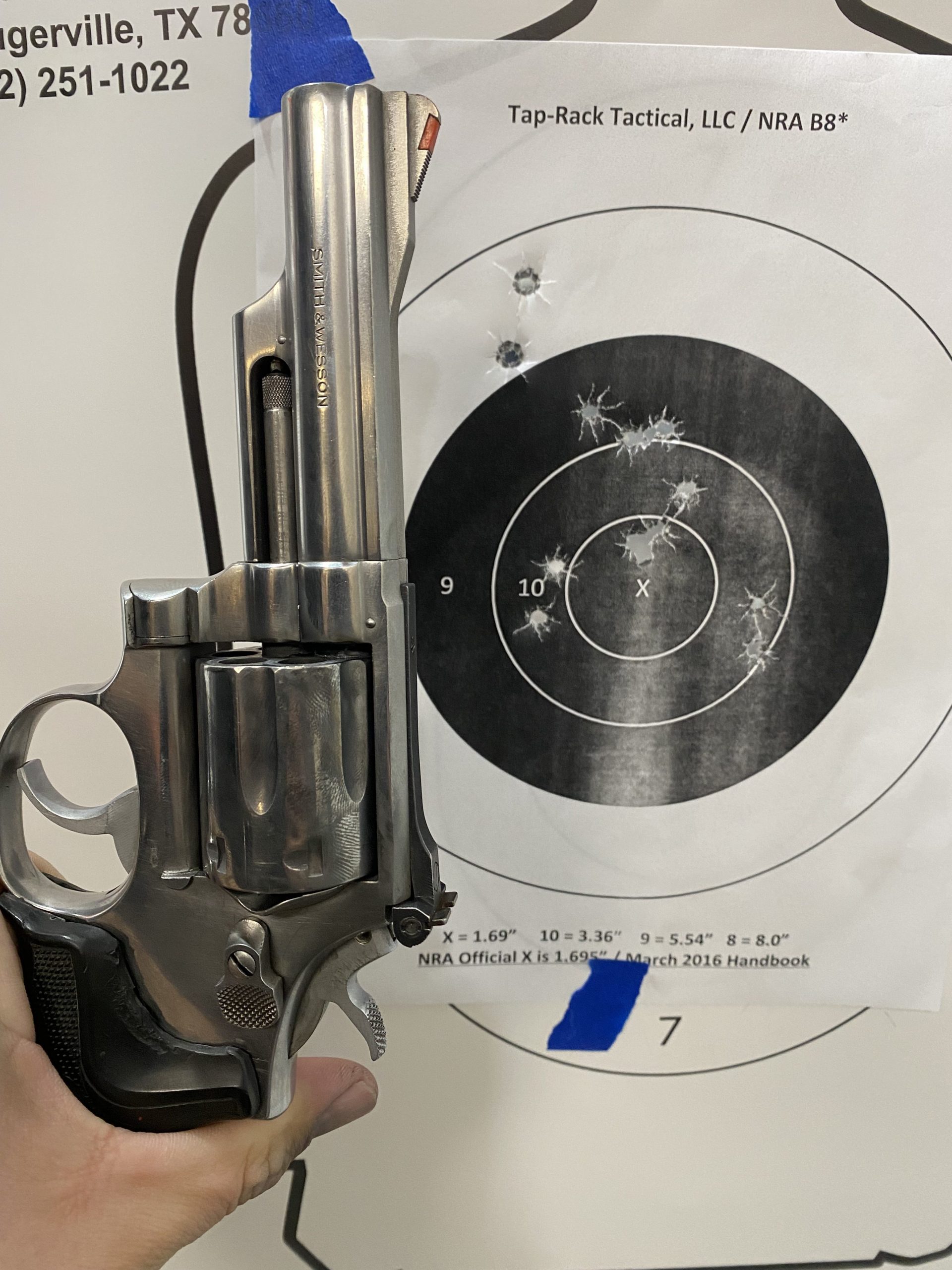

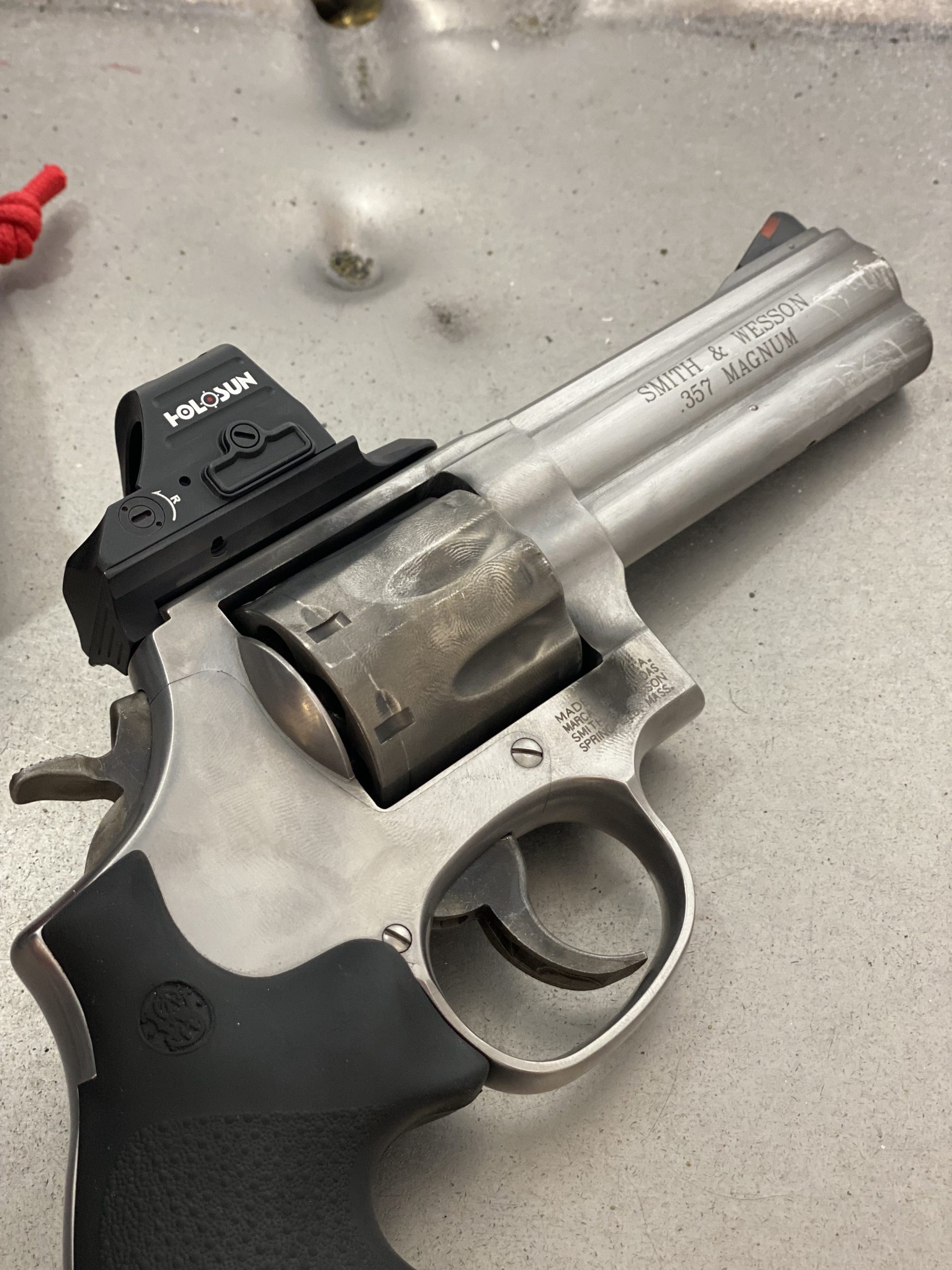

My Latest Madness

A few months ago and under poor impulse control, I accidentally bought a used Smith and Wesson 686-5 revolver with a four inch barrel. This fifth revision does not have the maligned “safety lock” hole on the frame, but it does have the more modern frame mounted firing pin arrangement which is actually easier to upgrade and mitigates failure from the exposed firing pin being damaged on the face of the hammer. This revolver is also new enough that it comes with a topstrap that is drilled and tapped from the factory. This only meant one thing! Time to dress up this L-frame with a red dot! My friend Caleb Giddings suggested an Allchin mount which I subsequently purchased. I picked out a mount with the Holosun/RMR/SRO footprint for my HS407C. Installing both the Allchin mount and the Holosun directly on top of the mount was extremely easy.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I had Tony Mayer of JM Custom Kydex bend me a dot cut appendix L-frame holster to further enable my madness. An L-frame revolver with rubber boot stocks is a very tall gun to conceal in the appendix position, but I am not too concerned about that as this gun and holster is solely for my pleasure. I can’t wait to sight this dot in and shoot some drills with this holster on a range bay. Life is too short to not enjoy shooting revolvers. And you can’t argue with the trigger control that carries over to other types of pistols.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Just wait until tell you how I really feel about 1911s.