Last year, I got wind of the Long Range Shooting Handbook written by Ryan M. Cleckner while listening to Hornady’s excellent podcast on all-things rifles. As a writer, I consider myself well-versed in pistol shooting. However, for long distance/precision rifles, I’m working on catching up to the level of knowledge I ought to have.

Putting in the legwork into my rifle education, a topic that can be daunting and mysterious, has been quite rewarding to date. Some of my favorite articles that I’ve enjoyed writing are about these topics: scopes, the rifles that use them, and their shooting.

As a perpetual student, Hornady’s own podcast is a great resource for rifle shooters of all skill levels to learn the intricacies of propelling small, neatly shaped pieces of copper and lead across space accurately. Cleckner, a lawyer by trade and veteran of the 75th Ranger Regiment and the GWOT, has also been a guest in a Hornady podcast episode where this book was mentioned. So I bought it and I genuinely enjoyed it.

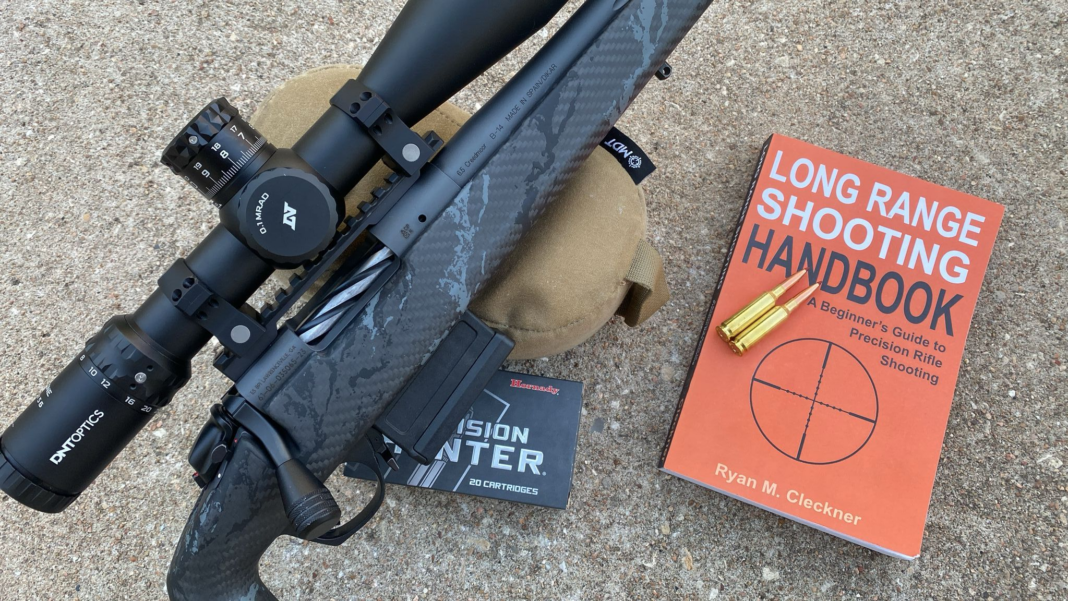

Long Range Shooting Handbook

Cleckner’s text found throughout this handbook is extremely detailed and comprehensively covers everything that pertains to rifle shooting–from breathing control to propellant characteristics. And even with the amount of technical information displayed between the Long Range Shooting Handbook’s pages, it’s easy to understand.

I also found it to be well written in the context of a handbook, specifically because Cleckner’s word choice itself isn’t overly technical and his sentences are easy for anyone to understand. This handbook sets out to serve both novice and expert shooter alike. In the text Cleckner even admits that he chose the book’s cover to be blaze orange so that it could easily be found in a rifle shooter’s gear bag while out in the field behind the scope and trigger.

Examples From The Text I Appreciated:

Parallax

In Chapter 5, Aiming Systems, Cleckner makes some time to explain the concept of parallax in rifle shooting. In my case, I have a rudimentary understanding of parallax and how to verify that one’s scope is parallax free. Hoever, articulating this phenomenon is a different matter altogether. In my years of being interested in firearms, it seems that parallax is something that’s poorly explained despite the fact that it’s crucial in making precise shots.

In this chapter for example, even I had no idea that parallax wasn’t a factor when shooting with iron sights. After all, there is no such thing as parallax adjustment for iron sights, so I never gave it much thought. But Cleckner goes on to explain that parallax isn’t an issue specifically because of the deliberate alignment between the target and both sets of sights. Since all three elements are lined up, this cancels out parallax.

I appreciate his explanation in describing “everything lined up” because he then explains what a parallax error inside a scope actually looks like. Specifically, the target’s image is focused at a different point inside the scope compared to where the shooter’s eye is looking (at the reticle).

The result is that the eye tends to focus on the reticle and then superimpose the reticle image over the misaligned target image which leads to a false correlation between the point of aim and the point of impact. Parallax error in scopes is all about misalignment.

On Page 64, Cleckner writes:

In order to remove the effect of parallax, and to have both the target image and the reticle clear, the focus location of the target image inside the scope must be changed so that it is at the same location as the reticle. You can adjust the target image’s focus location with your scope’s target focus or parallax adjustment. Both names for the adjustment are suitable. No, parallax is not the same as focus, but by adjusting the target’s focus, we are removing the effect of parallax.

Finally, I knew that scope focus and parallax adjustment weren’t technically the same thing. But through the handbook I learned focus removes parallax, as it were.

Angular Units Of Measure

Chapter 9 of the Long Range Shooting Handbook is all about units of measurement in shooting. Cleckner covers linear units such as yards and meters in addition to quintessential angular units of measure like MOA and milliradians.

Even though the handbook’s copyright is from 2016, I like how he dabbles a little into G1 and G7 ballistic coefficients—important figures that the latest in ballistic apps ask the shooter for. Likewise, much like craft beer brags about IBUs and gravity on the label, it seems like all factory-loaded match grade rifle cartridges boast their ballistic coefficients on their box.

However, I liked Chapter 9 because of what Cleckner said about milliradians:

On Page 133, he writes:

I have heard many people argue over whether 1 Milliradian equals 1 meter at 1000 meters or whether it equals 1 yard at 1000 yards. They are both right! 1 Milliradian equals 1/1000th of any distance. It is 1 inch at 1000 inches and 1 mile at 1000 miles. It doesn’t matter what unit of measurement you are using as long as you keep using that same unit of measurement.

Somehow, I either forgot or missed this part of the memo about using mils. But now it makes sense why many believe that milliradians are specifically a “metric” angular unit of measurement. They aren’t but the numbers happen to divide evenly.

The Takeaway

The Long Range Shooting Handbook is full of great examples about every aspect of shooting, from the Day 1 basics to the more advanced but essential topics. Even though this handbook was published in 2016, I won’t call it dated.

Sure, this handbook hit the scene just as things like the 6.5 Creedmoor cartridge or PRS style shooting were starting to become “things.” And no, the book won’t discuss the latest in ballistic solvers or chronographs like the new Garmin. However, the lessons and wisdom found within the pages of this handbook are more than relevant today.

The Long Range Shooting Handbook is the type of book I would have loved to have come across when I was 15 years old in high school; I know I’d have devoured it from cover to cover.