Recently I had the pleasure of attending an outdoor workshop that was extremely interesting and useful, so I’m here to tell you about it.

The name of the workshop/class was “Tree Identification for Foragers”, presented by Adam Haritan of Learn Your Land. And the workshop was hosted by Erik Kulick of True North Wilderness Survival School.

Anyone who has read my scribbling here at GAT knows that I am interested in food growing, food preservation, and also food foraging. With foraging thus far I have learned a bit on my own, and a bit by osmosis from my forestry-major daughter. This workshop was my first formal instruction on the topic. I use the term “formal” loosely because the workshop was very open to questions and inquiry and was not at all a stiff classroom environment. It was nonetheless very valuable to me.

The location for this outdoor workshop was a 600+ acre park in suburban Pittsburgh called Hartwood Acres. Many of those acres are wooded, which provided many examples of the trees that we learned about during the day.

The focus of the workshop was not “just” tree identification, but how this identification can tell you so much more about the soil, landscape, and ecology of the land in which it is growing. It was a sort of “holistic” approach which I found very interesting.

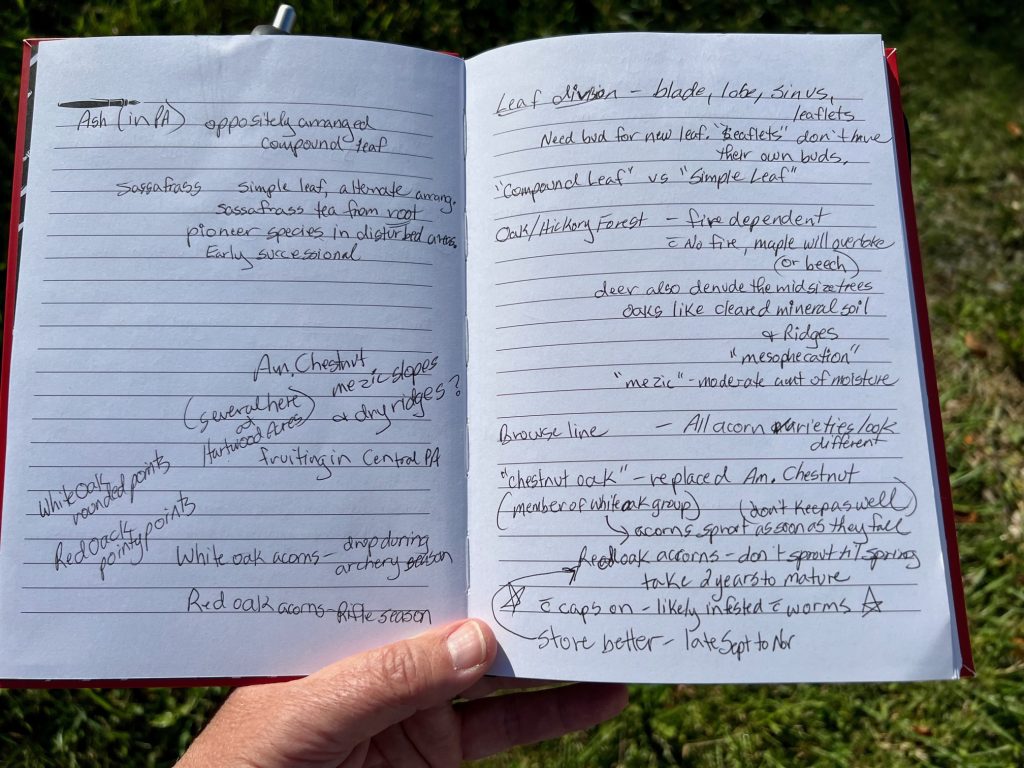

During the four hour workshop I took almost nine pages of notes in my “field notebook” that I purchased at Ollie’s the day before the class. (Yes, I’m cheap.) I’ll have to go back through those notes to type out complete sentences and connect info that I strung together with arrows, and clarify some spelling and things that I sort of scribbled as I walked. I would have taken more notes, but I also wanted to examine the specimens, taste them, take photos, and listen more closely, and it was challenging to juggle all of it at once.

One of the first things we learned was the framework to use to be able to identify trees. I think the first he mentioned was having a basic idea of what grows in your area. That way you don’t have to plow through hundreds of things in the guidebook that couldn’t even be a possibility based upon your location. Then we learned about leaf branching arrangements (opposite vs alternate vs whorl) and leaf structure (simple vs compound), which informed a flow sheet approach for identifying the tree you are interested in. That was just the first trickle from the fire hose of information which followed.

There were several highlights of the day for me, one of which was the introduction and sampling of “Nannyberry”. This was something I’d never heard of before in 60 years of living in the East. I found a nursery online that carries them and I may have to have a couple for my yard as they are native and I don’t yet have any late fall berries for my attempt at a multi-season foodscape. Nannyberry is also listed as fairly deer resistant, which I definitely need. Though they have a large pit, Nannyberries are sweet and taste a bit like raisins. I’m going to have to keep an eye out for them in the wild as well.

But the biggest highlight was seeing not just one, but two surviving American Chestnut trees in Hartwood Acres! As you may or may not know, American Chestnut has been all but wiped out in the last hundred years by a fungal pathogen which arrived from Asia in the early 1900’s. It used to be a key species in America for not only hardwood harvest, but also abundant nut production for both human and wildlife consumption. Many old barns have huge main beams that are American Chestnut. Its niche has since been supplanted by oak and hickory, but neither are as prolific nut producers as American Chestnut was historically.

There were multiple other learning experiences throughout the day. One such learning experience came when I stabbed a finger on the spines of a Spanish chestnut husk. Thereafter I used a stick to get at the nut while protecting my digits (d’oh!). I also learned how to tell the difference between a toxic, inedible horse chestnut or “buckeye” and an edible “sweet chestnut”. According to Adam, the edible varieties have a starburst pattern on the nut, and the inedible types do not.

Additionally I learned that Hawthorn fruits look like rose hips. Hawthorn is technically a type of apple and apples are in the rose family. So that explains that – who knew? I also learned there was such a thing as “Pignut Hickory”, which was historically made into a nut milk by native tribes and settlers.

I cannot recommend this class enough for those who are interested in learning more about the trees and landscape around them. I hope at some point there might be a “Level 2” to this course. In the meantime I need to keep working on and polishing my skills!

For those with long memories, True North was where I had planned to take a Basic Land Nav course last year, but then didn’t feel well and had to cancel. So now that I am retired, that class is back on my agenda for the coming year.

Learn Your Land offers an online “Trees in All Seasons” course which I also plan to sign up for in the coming months.

If you are interested in learning more about the outdoors and/or survival, taking some instruction from either of these organizations would be well worth your while.

My personal learning curve continues!