Buckshot: The elementary type of ammunition that makes the shotgun a shotgun. At its most basic level, buckshot is nothing more than a payload of 8 to 15 lead pellets that spread over an effective pattern to distances of approximately 25-30 yards. Generally speaking, buckshot ammunition is the go-to for defensive and tactical shotgun use, and not to mention large game hunting. The concept of loading a firearm with several projectiles in order to spread in a pattern to hit the intended target is nearly as old as the concept of the firearm itself. By the time flintlocks became the norm, the concept of the shotgun also started to become codified in different firearm designs. Two notable examples from this period would be the blunderbuss and the fowling piece.

MODERN BUCKSHOT SHOTSHELLS

Shotgun ammunition operates at relatively low pressures, which is why shotshells were once also made from cardboard or paper. Modern hulls are made from plastic for convenience and water resistance. That said, there are four main components to a modern buckshot cartridge: the powder charge, the wad, the buffering (called grex), and the pellets. All four play a role in consistency and effective patterning. For the purposes of this writing any loads or shotshells are implied to be standard 2.75-inch 12 gauge cartridges only. Because the Twelve is king, 12-gauge buckshot ammunition will also have the most advanced options on the market today. Ideally, a buckshot load will pattern consistently and penetrate deeply enough to stop threats. Even the lowest grade buckshot will not have a cone-of-death pattern, and employing shotguns successfully means they have to be aimed. Failure of doing so will result in misses, even in close quarters.

POWDER, VELOCITY AND GREX

Because of lower pressures, many powders used for loading shotshells cross over into handgun cartridges and vice-versa. This article is not about shotgun powder formulations, per se. However, the quantity of powder in a load does affect velocity and it bears mentioning that for buckshot, sometimes less [velocity] is more. For example, the tactical buckshot with some of the tightest patterns on the market currently (12-gauge 8 Pellet Federal Flite-Control LE 13300) only has a muzzle velocity of 1145 feet per second. For comparison, the typical dove, clay or all-around sporting birdshot load averages 1200-1250 fps of muzzle velocity. A gentle powder charge leads to better patterning because pushing the pellets too fast causes them to crash and bump into each other and deform while traveling down a shotgun’s bore. Past the muzzle, these deformities will cause pellets to fly erratically and deviate away from the main shot column.

To protect pellets from deforming, modern buckshot loads also feature grex, a type of crushed down plastic that looks like coarse salt and functions to buffer and protect pellets individually as the shot column travels down the bore. Not all buckshot loads will have grex, but shooters can expect to find it in any premium hunting or tactical shotshell product line.

WADS AND PELLETS

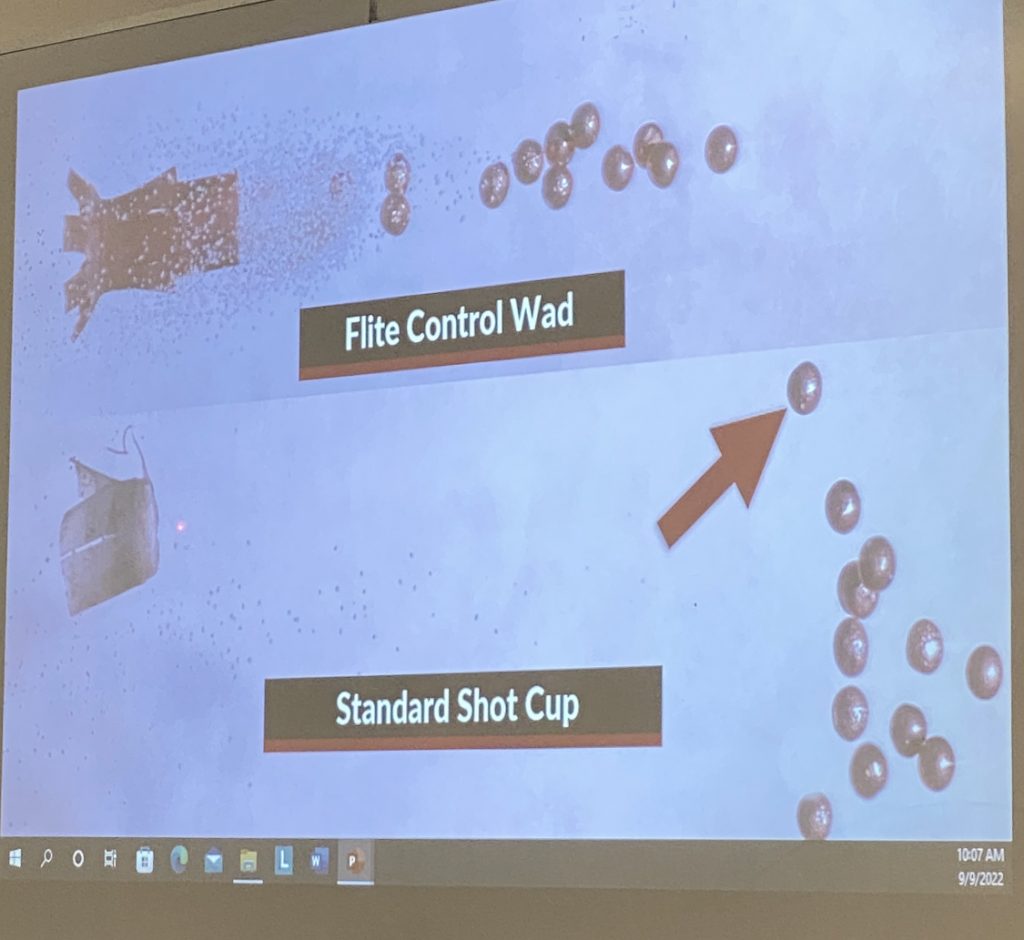

Shotgun wads for buckshot can be as simple as a clump of horsehair or a round felt cut-out, or they can be as sophisticated as the shuttlecock resembling plastic wads that are the Federal Flite-Control or Hornady Versatite wads. Those basic felt or horsehair wads separate the shot from the powder but don’t do much more. More modern plastic wads are cup shaped and have petals, so they cradle and envelop the shot column inside the hull. During firing, modern wads stay together with the pellets while they exit the shotgun’s bore. They also exit the muzzle at the same time and fly together for some distance until individual pellets start to fan out and the wad’s petals open up until the wad itself eventually deviates completely from the flight path. Because they keep the shot column together (typically 8 or 9 pellets for standard 00-buckshot loads), wads have a large bearing on shotshell consistency and patterning ability. The more basic felt or horsehair wads don’t do much besides separating the shot from the powder, and typically these loads have an effective distance of 15 yards at best. It doesn’t help that pellets in these loads are not buffered with grex or plated. For generations, shotgun shooters had to make do with such marginal buckshot loads. And this is probably a reason why the shotgun perhaps fell from favor compared to carbines. Ineffective shooting techniques that did not manage recoil correctly also did nothing to help this wonderful weapon’s case. One of the best things to happen to modern shotguns is the Federal Flite-Control wad. The Flite-Control wad is available in some of Federal’s more premium law enforcement and defensive shotshell product lines. Buckshot using this wad generally patterns well regardless of a shotgun’s barrel length, make or model. In some cases, it can also nearly double a given shotgun’s effective range. This wad looks like a shuttlecock and is designed to peel back from the column in flight in such a way that minimally disturbs pellets. Of course, Flite-Control loads include plated pellets and are buffered with grex.

Depending on application, buckshot pellets range from sizes #4 (0.24” cal) to 0000 (0.39” cal). For defensive and tactical purposes, the standard pellet size for 12 gauge loads has always been the 00 “double-aught” (0.33” cal). Standard 2.75 inch double-aught buck loads can have payloads with as little as 8 pellets or as many as 12. Cheap buckshot loads are usually loaded with “bare” pellets while the pellets in premium loads are hardened and copper (sometimes nickel) plated. In addition to being buffered with grex, plated pellets also have a better chance of resisting bumping and knocking and becoming deformed during firing.