[Ed: This is the inspiring true story of men who took up arms to defend their families, communities and movement during the 1960’s Civil Rights conflicts. It reminds us why firearms must be in the people’s hands when authoritarian government would maintain its monopoly of arms. DRGO friend Philip Smith, President of the National African-American Gun Association, originally published this in its latest member newsletter.]

The Deacons for Defense and Justice was an armed African-American self-defense group founded in November 1964, during the civil rights era in the United States, in the mill town of Jonesboro, Louisiana. On February 21, 1965—the day of Malcolm X‘s assassination—the first affiliated chapter was founded in Bogalusa, Louisiana , followed by a total of 20 other chapters in this state, Mississippi and Alabama. It was intended to protect civil rights activists and their families. They were threatened both by white vigilantes and discriminatory treatment by police under Jim Crow laws. The Bogalusa chapter gained attention during the summer of 1965 in its violent struggles with the Ku Klux Klan .

Founding of The Deacons for Defense

African Americans were harassed and attacked by white KKK vigilantes in the mill town of Jonesboro, Louisiana in 1964, also burning down five churches, their Masonic hall and a Baptist center. Given the threat, Earnest “Chilly Willy” Thomas and Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick founded the Deacons for Defense in November 1964 to protect civil rights workers, their families and the black community against the local KKK. Most of the Deacons were veterans with combat experience from the Korean War and World War II.

In 1964, during Freedom Summer and a period of extensive voter education and organizing for registration, especially in Mississippi, the Congress of Racial Equality established a Freedom House in Jonesboro. It became a target of the Klan who resented white activists staying there. Because of repeated attacks on the Freedom House, as well as the church burnings, the Black community decided to organize to defend it. Thomas was one of the first volunteers to guard the house. According to historian Lance Hill, “Thomas was eager to work with CORE, but he had reservations about the nonviolent terms imposed by the young activists.”

Thomas, who had military training, quickly emerged as the leader of this budding defense organization. He was joined by Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick, a civil rights activist and member of SCLC, who had been ordained that year as a minister in the Pentecostal Church of God in Christ .

During the day, the men concealed their guns. At night they carried them openly, as was allowed by the law, to discourage Klan activity at the site and in the black community. In early 1965, Black students were picketing the local high school in Jonesboro for integration. They were confronted by hostile police ready to use fire trucks with hoses against them. A car carrying four Deacons arrived. In view of the police, these men loaded their shotguns. The police ordered the fire truck to withdraw. This was the first time in the 20th century, as Hill observes, that “an armed black organization had successfully used weapons to defend a lawful protest against an attack by law enforcement.” Hill also wrote: “In Jonesboro, the Deacons made history when they compelled Louisiana governor John McKeithen to intervene in the city’s civil rights crisis and require a compromise with city leaders — the first capitulation to the civil rights movement by a Deep South governor.”

After traveling 300 miles to Bogalusa, in southeast Louisiana, on February 21, 1965, Kirkpatrick, Thomas and a CORE member worked with local leaders to organize the first affiliated Deacons chapter. Black activists in the company mill town were being attacked by the local and powerful Ku Klux Klan. Although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been passed, blacks were making little progress toward integration of public facilities in the city or registering to vote. Activists Robert “Bob” Hicks (1929-2010), Charles Sims, and A. Z. Young , workers at the Crown-Zellerbach plant (Georgia-Pacific after 1985, later acquired by another), led this new chapter of the Deacons for Defense.

In the summer of 1965, they campaigned for integration and came into regular conflict with the Klan in the city. The state police established a base there in the spring in expectation of violence after the Deacons organized. Before the summer, the first black deputy sheriff of the local Washington Parish was assassinated by whites.

The militant Deacons’ confrontation with the Klan in Bogalusa through the summer of 1965 was planned to gain federal government intervention. “In July 1965, escalating hostilities between the Deacons and the Klan in Bogalusa provoked the federal government to use Reconstruction-era laws to order local police departments to protect civil rights workers.”

The Deacons also initiated a regional organizing campaign, founding a total of 21 formal chapters and 46 affiliates in other cities.

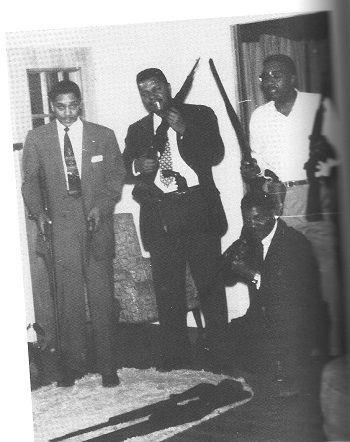

Members of The Deacons for Defense

The Deacons had a relationship with other civil rights groups that practiced non-violence. Such support by the Deacons allowed the NAACP and CORE to formally observe their traditional parameters of non-violence.

The Deacons were instrumental in other campaigns led by the Civil Rights Movement. Activist James Meredith organized the June 1966 March Against Fear, to go from Memphis, Tennessee , to Jackson, Mississippi. He wanted a low-key affair, but was shot and wounded early in the march. Other major civil rights leaders and organizations recruited hundreds and then thousands of marchers in order to continue Meredith’s effort.

According to in a 1999 article, activist Stokely Carmichael encouraged having the Deacons provide security for the remainder of the march. After some debate, many civil rights leaders agreed, including Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Umoja wrote, “Finally, though expressing reservations, King conceded to Carmichael’s proposals to maintain unity in the march and the movement. The involvement and association of the Deacons with the march signified a shift in the civil rights movement, which had been popularly projected as a ‘nonviolent movement.”‘

FBI investigation begins in 1965

In February 1965, after an article in The New York Times about the Deacons in Jonesboro, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover became interested in the group. His office sent a memo to its Louisiana field offices: “Because of the potential for violence indicated, you are instructed to immediately initiate an investigation of the DDJ [Deacons for Defense and Justice].” As was eventually exposed in the late 1970s, the FBI established the COINTELPRO program, through which its agents were involved in many illegal activities against organizations that Hoover deemed “a threat to the American way”.

The Bureau ultimately produced more than 1,500 pages of comprehensive and relatively accurate records on the Deacons and their activities, largely through numerous informants close to or who had infiltrated the organization. Members of the Deacons were repeatedly questioned and intimidated by F.B.I. agents.

Harvie Johnson (the last surviving original member of The Deacons for Defense and Justice) was interviewed by two agents during this period. He said they asked only how the Deacons obtained their weapons, never questioning him about the Klan activity or police actions they were responding to.

VIDEO ON DEACONS OF DEFENSE CLICK BELOW:

Most histories of the Civil Rights Movement tend to overlook such organizations as the Deacons.

There were are several reasons for this: First, the dominant ideology of the Movement was one of non-violence unless they were attacked.

Second, threats to the lives of Deacons’ members required them to maintain secrecy to avoid terrorist attacks. In addition, they recruited only mature male members, in contrast to other more informal self-defense efforts, in which women and teenagers sometimes played a role. Finally, the organization was relatively short-lived, fading by 1968. In that period, there was a national shift in attention to the issues of Blacks in the North and the rise of the Black Power movement in 1966. The Deacons were overshadowed by The Black Panther Party, which became noted for its militancy.

.

.

— DRGO Editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

All DRGO articles by Robert B. Young, MD